Thanks for letting us enjoy your trip. The peat plateau’s formation is fascinating.

-

Happy Establishment of the Nobel Prize (1895)! 🏅🧨

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Seal River in Northern Manitoba

- Thread starter PaddlingPitt

- Start date

- Joined

- Aug 21, 2018

- Messages

- 1,729

- Reaction score

- 1,919

Stay tuned? I'm freakin' glued to the monitor. Absolutely riveting, great photos too. What film/camera were you using? And how in the world can you remember all the details? You must have had some terrific notes...

Can't wait for the next installment!

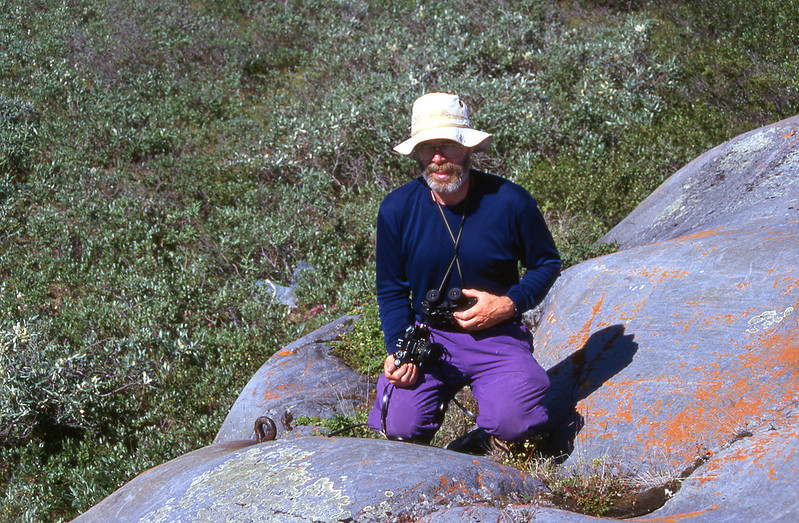

Back in 1997, Stripperguy, we were still shooting film. I was very slow to change to digital. I don't like change. I was using a Canon camera. Kathleen was using a Minolta. I was still shooting the traditional Kodachrome 64.

We once attended a slide show in the early '90s where the guy's images of water and sky were superb. We asked him what kind of filters he was using. Not filters, he said, "I shoot Fujifilm Velvia. It saturates blues and greens." Ever since then Kathleen shot Velvia. I think 100, but it could have been 50. Of course, we both used polarizing filters.

on our trips, I write down the day's events in my diary. Full prose, not just notes. When we get home, I flesh out the notes more completely. This was necessary for our own memories, as well as preparing for slide show presentations in the greater Vancouver area. It's amazing when I look back on these descriptions how often I say, "I don't remember that."

- Joined

- Aug 21, 2018

- Messages

- 1,729

- Reaction score

- 1,919

After 90 minutes the fog lifted to a grey sky as the headwind intensified. After struggling until a little after 4:00 p.m., we camped on a small island, approximately 17 km (10 miles) downriver from last night’s camp. I felt very content in our home stretched along the banks of the Seal River. For me, it only takes a few days of living—in the open—on the river before I become enveloped by quiet exhilaration. It is as though the very power of the earth and the wind penetrate to my soul, and I never feel so free, so strong, and so alive as when I am paddling down a wilderness river.

We enjoyed a stroll down the island's inviting sandy beach before our supper of chili and tea.

We stopped to appreciate and photograph plants such as Mouse-ear Chickweed

And Rock Cranberry. Rock Cranberry is also more commonly called Ligonberry. Kathleen says she prefers Rock Cranberry as more descriptive. And, as she asks, somewhat rhetorically, “Who knows what a Ligonberry is anyway?” Apparently, Kathleen doesn’t.

For the first time on the trip, the entire day was cool, reaching a high of only 12 degrees C (54 degrees F). With the wind and fog, we felt cold and longed for some heat. We would even have welcomed the 38 degree heat (100 F) that afflicted us two days ago. By 9:30 p.m. fog completely surrounded our camp once again.

We made no progress the next day, as rain continued, nearly without interruption, since 4:00 a.m. that morning. We spent the day in the tent, reading, napping, snuggling, snacking, and waiting for the rain to leave us alone. We also worried about the difficulty of the 13 rapids that still remained between us and Hudson Bay. Named rapids always worried us. We still had to deal with Deadly Rapids, the 14 km (8.5 mile) Felsenmeer Rapids and Deaf Rapids.

During our second morning on the island, Kathleen and I reviewed our Plans A & B for reaching Churchill. As you remember, we had allowed 4 days to paddle the approximately 70 km (43 miles) to Churchill. We intended to put on the water two hours before high tide, and take off 2 hours after high tide. We could travel approximately 15 km (9 miles) in 4-hour sprints. At two tides per day, we needed only 4 of 8 tides to bring favourable paddling weather. This was Plan A, as suggested by the late Victoria Jason.

During the past three mornings, however, the fog had been too dense to risk paddling on the bay, such that we would have lost the morning tide. Also, the afternoons had been windy, perhaps preventing us from paddling the bay on the afternoon tide. The closer we got to Hudson Bay, the worse the weather had become. We had now spent our last tentative “rest day” in camp, and would no longer have a full day at Hudson Bay to assess the potential for paddling to Churchill.

So it seemed that our plan for sprinting to Churchill was in some jeopardy. For the first time, Kathleen and I talked seriously about pursuing backup Plan B to paddle 6 km (3.7 miles) north, up the Hudson Bay coast to the Seal River Lodge. We were happy that we confirmed with Mike, just before leaving Vancouver, that the lodge would be open on July 15, and that we might arrive between July 16 and July 19. He again encouraged us to paddle up to the lodge.

Before heading downriver, though, ever closer to the malevolent Bay, we took one last walk along the beach to enjoy the morning mist and stillness.

We successfully paddled the 14 km of continuous rapids known as the Felsenmeer—German, for “sea of rock”—which included the Class IV Deadly Rapids. Difficult rapids never seem to have friendly names. There are no Class IV rapids known as Winnie-the-Pooh Rapids, or Yummy-Chocolate-Pudding Rapids. No. Difficult rapids always have ominous names, such as “Deadly.”

Anyway, when we arrived here at Deadly Rapids, we beached on river right to scout. The rapids were, after all, called “Deadly.” Kathleen and I consider ourselves to be prudent canoeists. Prudent canoeists scout Class IV rapids called “Deadly.” Besides, the rapid truly did look serious as we approached by canoe.

We scrambled down the rocky shore in a light rain and a dense mist. “Deadly” had high volume in the middle and two serious ledges on river right halfway down. We agreed on a plan to ferry out very near to the large waves in river centre. This would put us beyond the immediate threat of going over the ledges. Then, to avoid being swept into the large waves in mid-channel, we would turn down and head hard right to eddy out just below the second ledge halfway down the rapid. Only two necessary moves. Three, if you count the eddy turn below the ledge. We should be able to do it.

We both felt confident as we climbed back into the canoe, snugged our spray skirts over the cockpit coaming, and began our ferry out to river centre. I stroked hard all the way, worried about those ledges. From the bow, Kathleen yelled out, “Michael. What are you doing? Head down. Go right. We’re too far out!”

“But where are the ledges? I can’t see ‘em.”

“Just go right!”

I went right, as Kathleen instructed. She knows what she’s doing. Still, though, I asked one more time, “Where are the ledges?”

“We’re OK. Just keep going right.”

Moments later we eddied out behind the ledge and rested in the calm water.

“Michael. What was the matter? Why couldn’t you see those ledges?”

“My glasses were all fogged up because of the rain. I couldn’t see, so I took them off.”

I should tell you that I wear glasses for a reason. With my foggy glasses off, I still couldn’t see all that well.

Apparently telling the truth, doesn’t always impress my paddling partner. In retelling the story, Kathleen likes to say, “Next time you’re going to run a Class IV rapid blind, you could at least tell me so I can get out of the boat.”

She didn’t actually say that at the time, but it makes a good story. And, she actually might have been thinking it at the time.

We’re camped this evening on a beautiful tundra ridge, adorned with clooudberries, on the left bank, approximately 8 km (5 miles) downstream from Deadly Rapids.

The day had been generally overcast, with some fog, but mostly dry and mostly calm. We ran all the rapids successfully, and were certainly pleased with ourselves. Only six more rapids before Hudson Bay, which was now only 20 km (12 miles) down the Seal River. Deaf Rapids, right near the bay, is alleged to be the most difficult of the entire journey. Tomorrow, we intend to camp on Hudson Bay itself, and would need to decide between Plans A & B the following morning.

During the day, we saw a few more seals and several flocks of elegant Tundra Swans. By 9:30 p.m., our tent was once again enveloped in mist drifting over from Hudson Bay.

The cloudberry was one of the favourite fruits of northern people, second only to blueberries. The fresh fruits did not last long, and were often preserved in oil or fat.

I woke just before 5:00 a.m. and was encouraged to see a small patch of blue piercing the dense fog that surrounded our camp all night. We enjoyed another bannock breakfast, photographed an elegant Northern Bog Violet, and put on the water at 9:30. In a little over an hour, we reached the entry rapid to the Seal River delta. The sun hinted that it might break through to dissipate the mist. The fog reasserted its dominance, however, and we peered into the grey gloom as we ran downriver.

This last stretch of the Seal River had many islands and bays that made it difficult to locate ourselves on the map, which added to our uncertainty about how close we might be to Deaf Rapids.

The fog and mist grew even more dense, with visibility sometimes down to only 50 m (yards). But we hoped to reach Hudson Bay today, and we paddled on, until it became obvious that we were running rapids based primarily on sound, intuition and reaction. Not very wise, as we definitely heard, but could not see, what sounded like a very large rapid just downstream. We pulled off the river to have a better look at the rapid from shore. This was a good idea—in principle. We still couldn’t see the rapid, however, because of the dense fog. We portaged across a wet, slippery boulder field, about 500 m (yards) around the rapid.

We paddled on. Straining to see. Straining to hear. At one point, because we couldn’t see any river banks, we thought that perhaps we had entered the mouth of the Seal River and were approaching Hudson Bay.

Just wishful thinking on our part, though. We couldn’t see river banks only because fog obscured them. And besides, it was very unlikely, even ludicrous, that we had paddled through Class IV Deaf Rapids without knowing it.

We continued paddling until we heard a threatening roar downriver. “This could be Deaf Rapids, Michael.”

“Yeah. Could be.”

Visibility had again dropped to only 50 m (yards). We headed to shore. Best to run Deaf Rapids when we could actually see Deaf Rapids. You might remember the incident at Deadly Rapids.

So, we ended our paddling day at 6:30 p.m. to set up camp on a very wet and boggy flat that undulated like a waterbed. Kathleen heated soup for supper, after which we crawled into the tent for tea.

Our very soggy, boggy home for the night was among the all-time worst campsites I have ever “enjoyed.” Even so, I was glad to have stopped, and to rest from struggling against fog, wind and rapids. We didn’t reach Hudson Bay today, and we thought we were still about 2 km (1 mile) above Deaf Rapids. Despite these adversities and anxieties, however, we were thoroughly enjoying our trip. Life on the river might not always be easy, but life on the river is always simple. Like all obstacles, we would deal with Deaf Rapids when we got there. We would run them if we could. We would portage them if we must. We would just have to wait to see what it looked like when we arrived tomorrow morning. Based on the persistent fog of the last days, Plan B was beginning to look likely. Maybe we would even paddle all the way to the Seal River Lodge tomorrow. If Deaf Rapids were just downstream, then we were only 10 km (6 miles) from the Seal River Lodge.

We left our soggy, boggy, undulating, waterbed camp at 10:00 a.m., beneath a low sky, but no mist on the water. We ran two rapids down to Deaf Rapids, and got out to scout on river right. Very high, threatening waves throughout. From our vantage point, it looked like there was a potential “sneak route” right up against the bank on river left.

“Do you want to ferry over there, Kathleen, and see what it’s like?”

“No. I want to portage.”

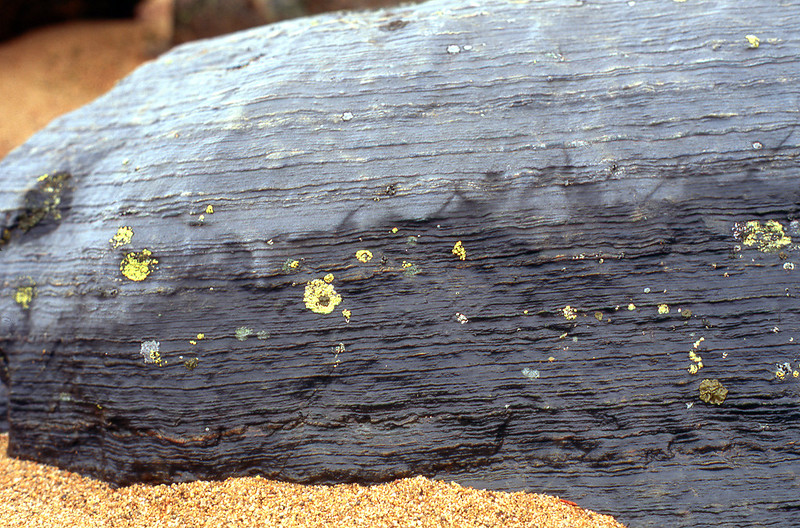

We lugged all of our gear past Deaf Rapids on a fairly well-defined trail through low shrubs. We stood next to our canoe, and stared to the east, across the mouth of the Seal River, which was filled with ledges everywhere. The Hudson Bay shoreline has been rebounding at a rate of about 0.5−3.0 metres (2-10 feet) per century since it was released from the weight of the ice that covered this landscape during the last glacial advance. This rebounding has created numerous, jumbled, haphazard ledges in virtually all directions. No obvious route existed through this last obstacle between us and Hudson Bay.

Kathleen and I picked our way east for another 45 minutes through the maze of ledges, rocks and rapids. And then, on July 16, two weeks and nearly 280 km (175 miles) after leaving Shethanei Lake, we finally paddled into Hudson Bay, where we startled half a dozen seals sunning themselves on the rocks.

We filled our water bottles and plastic water jug with the last fresh water from the Seal River, paddled north around the point, and reached Jack Batstone’s plywood shack at 5:00 p.m., only 25 minutes before high tide. Excellent timing on our part, even if not entirely planned. Jack operated a business that shuttled canoeists from the mouth of the Seal River down to Churchill. Canoeists call Jack to let them know when they would like to be picked up. Before leaving Vancouver, I had talked to Jack about the cost of staying at his shack.

"Will I be picking you up?"

"No. We might paddle to Churchill, or we might paddle up to the Seal River Lodge."

"Then you can't stay."

Anyway, Kathleen and I pulled the canoe high up on the beach, tied it to some willows, and walked up to the shack. No lock on the door. No one home. We moved in. Yes, I remember that Jack said we couldn’t stay here unless he was picking us up. I also remember that he built this plywood shack so that his clients didn’t get eaten by polar bears. Even though we weren’t Jack’s clients, we still didn’t want to get eaten by polar bears. And besides, when we get to Churchill, we’ll find Jack and offer again to pay him for our night’s accommodation. I promise.

We thoroughly enjoyed a spaghetti supper, and congratulated ourselves with brandy. We lay snug and warm in our sleeping bags, and discussed Plans A & B. Today had been relatively calm, with a few minutes of sunshine. Perhaps we should opt for the more exciting Plan A, to paddle to Churchill. The wind, however, seemed to be intensifying. Perhaps we should pursue the more prudent Plan B, to paddle to the Seal River Lodge. Either way, we would’t start paddling until about two hours before the evening high tide at 6:30 p.m. So we had all day tomorrow to decide.

Last edited:

Wonderful pictures and a great story! Thanks so much for posting.

- Joined

- Aug 21, 2018

- Messages

- 1,729

- Reaction score

- 1,919

We slept late and savoured another great bannock breakfast in the morning sun—our nicest day in a week. High cloud—no hint of rain or fog. Just before low tide, at noon, we strolled down to where the water rose at yesterday’s high tide. Even through the binoculars, we couldn’t see any water out on Hudson Bay. Just rocks and mud. Truly impressive, as people had suggested to us. It was one thing to hear that the tides go out 10 km. It was quite another thing to actually see for yourself.

Hudson Bay is much more than just another ordinary bay. In fact, it is the world’s second largest bay, exceeded in size only by the Bay of Bengal. Hudson Bay’s maximum length and width equal 1,500 km and 830 km, respectively (930 miles and 515 miles). Its total area equals 1,230,000 km[SUP]2[/SUP] (470,000 square miles). For a Canadian perspective, Hudson Bay is nearly twice the size of my home province, Saskatchewan. For an American perspective, Hudson Bay is nearly three times the size of California (where I was born). Hudson Bay is shallow, with an average depth of only 100 m. The long fetch, with strong winds and shallow water would make very formidable and challenging canoeing.

We turned back toward Jack’s shack and saw a polar bear, much closer to the shack—and its safety—than we were. We didn’t want to run, and we certainly didn’t want to get any closer to the bear. So we just stood there and watched, with rifle in hand, as the bear slowly ambled north into the wind.

It stopped briefly to look at us, rolled in ome willows, and disappeared over a small ridge. We had seen many black bears and grizzly bears on previous backpacking and canoe trips. We had become accustomed to bears being black or brown. So startling to see a white bear for the first time.

We scurried over to the shack and stood outside to see if the bear were circling back. It seemed, though, that we were all alone. At least for the time being, anyway. We sat on the steps of the shack, sunning ourselves, sipping tea, and learning the names of some of the vibrant flowers dominating these scenic Hudson Bay Lowlands.

Marsh Ragwort

Purple Paintbrush

Sea-shore Chamomile

The weather continued to improve throughout the afternoon as we photographed plants and the landscape and watched the tide rising over the glacial rocks strewn all along the shore of Hudson Bay. Kathleen and I had both looked forward to reaching Hudson Bay. Now we needed to decide whether we would paddle south to Churchill or north to the Seal River Lodge.

Through the binoculars, the lodge looked very inviting. Even though the lodge was 6 km (3.5 miles) away, it seemed to tower above the rock-strewn mudflats. I’m not exaggerating. The lodge looked really tall. Really tall like a sky scraper. Let me explain with the following information provided by E. C. Pielou. I quote:

"Light travels slightly faster through warm air than through cold, causing a light ray, as it passes from cooler to warmer air, to curve back toward the cooler air. To somebody observing a distant object through air that is warmer above than below…it will be elongated vertically, making it seem taller than it really is. This is a superior image, seen across a cold surface, and the kind likely to be seen in the Arctic."

So, it was time for a decision. What would you do if you were part of our expedition? Here are the attributes of Plan A: paddle 70 km 43 miles) over four days, in 4-hour sprints south to Churchill, risking fog, wind, mudflats, rocky shores, polar bears, and extensive tides.

Here are the attributes of Plan B: paddle 6 km (3.5 miles) for one afternoon, north to the Seal River Lodge, where we could shower, sleep in a bed, eat prepared meals while sitting at tables, perhaps enjoy a glass of wine, share our stories with fellow guests, and then fly to Churchill.

You probably noticed that I asked what would you do in our situation. When Kathleen and I give our Seal River slide show, we always ask the audience to vote on what they would do. It’s generally nearly unanimous that the audience prefers Plan B, to paddle to the Seal River Lodge. This is what we expect.

Well, when we presented our first Seal River slide show to our Beaver Canoe Club, we phrased the question differently, in that we asked, “What should we (as in Kathleen and I) do?” Most of the audience preferred Plan A, to paddle to Churchill. After the presentation, while chatting with club members, I talked to Dan, who had raised his hand in favour of paddling to Churchill. “Would you really have paddled to Churchill if you had been on the trip, Dan?”

“No, but I wanted to see you paddle to Churchill.”

That’s why, ever since that first presentation, I always ask, “What would you do?”

So, if you were standing there with Kathleen and me at Jack Batstone’s shack, what would you recommend that we do?

That’s what I thought. So we’ve all decided on Plan B. We will paddle to the Seal River Lodge. It seemed prudent, and so much easier. We have experienced a very enjoyable trip down the Seal River. Let’s call this trip done, and go to the lodge. And we still get to paddle a little bit on Hudson Bay, even without canoeing all the way to Churchill.

Our decision made, we waited for the tide to return. Two hours and 45 minutes before high tide, we began carrying gear and canoe across the mudflats to meet the rising tide. We started to load the boat at 3:45 p.m., and set out in a slightly windy, choppy, swelling ocean toward the Seal River Lodge, clearly visible to the north.

After 1 hour and 45 minutes, the lodge was distinctly visible, but we couldn’t see any people. That struck us as odd. You would think that the lodge guests would be excited about a lone canoe paddling north. You would think that the lodge guests would be standing on the beach, waiting to welcome us, ready to offer us elegant glasses filled with wine.

We paddled on, a little perplexed. A few minutes later, we could see that the windows and doors of the Seal River Lodge were still boarded up with plywood. At 6:32, exactly two minutes after high tide, we paddled into the cove in front of the still vacant Seal River Lodge. We had executed Plan B perfectly, but now found ourselves in a bit of a predicament. We were a little less happy with Plan B.

Oh well, Mike told us that there was a radio phone in the kitchen. Too soon for us to start worrying. I removed two Robertson screws from a side door plywood shutter, and we entered the main lodge. (Yes, I had a Robertson screwdriver with me. I always carry a variety of tools in my repair kit. You never know.) We strolled over to the kitchen and saw the radio phone, exactly where it was supposed to be. This was good. Plan B was still working. We depressed the call button, and spoke into the transmitter.

“Two canoeists at Seal River Lodge. Over.”

No response. We tried again.

“Two canoeists at Seal River Lodge. Over.”

Again. No response. We studied the radio phone.

“There must be an on-off switch, Michael. Maybe this is it.”

Good. No reason to have left the radio on when there’s no one here. Plan B was still working.

We again depressed the call button and spoke into the transmitter.

“Two canoeists at Seal River Lodge. Over.”

No response. We tried again.

“Two canoeists at Seal River Lodge. Over.”

Again. No response. We turned off the radio phone.

Maybe we don’t know how to use the radio phone. I started to look for an instruction manual when Kathleen noticed that the radio wasn’t plugged in. That makes sense. No reason to plug it in when no one was there. We attached the radio phone to an adjacent battery, turned it on, and were rewarded with sounds and lights. This was very good. I was beginning to love Plan B.

We spent the next several minutes repeating ourselves.

“Two canoeists at Seal River Lodge. Over.”

We must have transmitted and then listened two dozen times. The last six times or so, we added greater urgency.

“Two canoeists STRANDED at the Seal River Lodge. Over.”

The radio remained silent. Perhaps no one was listening to the frequency. But then, Mike had told us to use the radio phone if he wasn’t there. He knew approximately when we were coming. He owned an ecotourism business. He must have been listening. Plan B was not looking as wonderful as it had only a few minutes ago.

Just then, Kathleen noticed (She notices everything, doesn’t she?) that the cable leading away from the radio phone led to a hole in the floor. The end of the cable, however, didn’t actually go through the floor but just lay there, not attached to anything. What could this mean?

I crawled under the lodge, found the other end, and poked it back up through the kitchen floor. The two ends seem to have been severed. The cable included an outer set of wires around an inner set of wires encased in a tube. This was not like electrical cord at all. Not like the cord I could just easily twist back together and then secure with electrician’s tape, which I always carry in my repair kit. I learned later that this set of wires was coaxial cable. Although I try to be prepared for anything, I don’t yet carry any equipment in my repair kit to splice coaxial cable back together. Call me ill-prepared if you want.

Nevertheless, we tried our best. I held the two ends together while Kathleen transmitted and listened a dozen or so times.

“Two canoeists STRANDED at the Seal River Lodge. Over.”

No response. Just silence. Obviously, the radio phone was not going to work. We don’t know why the cable had been severed. Perhaps one of the very numerous arctic ground squirrels had chewed the cable, just to see what it tasted like. Don’t know why the squirrels would do that. I can’t think of any other reason why the cable would have been severed, though. The damage must have happened over the winter, as certainly Mike would have fixed the cable had he known last summer or fall that it had been severed.

We now had no communication, no pre-arranged pickup, and were 76 km (47 miles) from Churchill with only 6 tides remaining before we were scheduled to be in Churchill. Besides that, we now had canoed 6 km (3.5 miles) on Hudson Bay and knew firsthand that it could be dangerous, even with relatively calm conditions. We had paddled broadside to the incoming tide, and struggled to avoid rocks and shoals, while still making progress along the shore. If there were high winds driving a surging tide, we could be forced broadside up against the rocks, where our canoe might pin, or even capsize.

Kathleen and I spread our sleeping bags on mattresses in one of the bedrooms and fell asleep, more than just a little uneasy about our situation. I had taken a decided dislike to Plan B. Maybe we should have tried to paddle to Churchill.

As I lay in bed, though, I also thought about the many highlights of our day. We had successfully paddled the open shore of Hudson Bay. For the first time in our lives, we had witnessed the effects of a superior mirage, which made the Seal River Lodge appear to be several stories high. And, best of all, during our morning walk, we had seen our first polar bear. Yes, despite being the only residents at the Seal River Lodge, Kathleen and I had enjoyed a good day. Maybe Mike would come to open his lodge tomorrow. He had likely just been a little delayed for some reason.

Last edited:

Holy cow, the suspense is killing me, even though I know you made it! I would have opted for plan B as well.

I was favouring Plan A right up to the point where I saw a) the polar bear, b) the massive boulder strewn tidal flats, and c) the polar bear. I was never a fan of the rather tight time allowance for Plan A either, so that put me off too. After the gut-check as mentioned I would totally commit to Plan B with no reservations whatsoever.

It's funny how an easy out becomes attractive, not so much because of any luxuries waiting but because the anticipated relief of finally feeling stress free. That change in attitude and reasoning can come on any trip anywhere. The "almost there" feeling starting a trip sometimes gives way to "almost home" nearing its conclusion.

Thanks for this TR PaddlingPitt & Co.

It's funny how an easy out becomes attractive, not so much because of any luxuries waiting but because the anticipated relief of finally feeling stress free. That change in attitude and reasoning can come on any trip anywhere. The "almost there" feeling starting a trip sometimes gives way to "almost home" nearing its conclusion.

Thanks for this TR PaddlingPitt & Co.

Last edited:

- Joined

- Aug 21, 2018

- Messages

- 1,729

- Reaction score

- 1,919

We weren't really feeling stress, Odyssey. We just needed to make a decision, and Plan B seemed the most prudent choice. But if you want to see stress, just stay tuned. Will probably post again tomorrow afternoon. I could do so tonight, but people will probably be watching the midterm election returns.

We weren't really feeling stress, Odyssey.

So you missed the part about the polar bear. Lol.

- Joined

- Aug 21, 2018

- Messages

- 1,729

- Reaction score

- 1,919

The prospect of camping with Polar Bears certainly factored into our decision, Odyssey. But it was not the over-riding factor. The possibility of multiple days of wind and fog were more serious concerns for us. And besides, we wanted to be treated like conquering heroes when we canoed up to the lodge. Everybody likes a little bit of being the center of attention, now and then.

As a fairly hard core introvert I think paddling 3 miles to a lodge might have seemed more stressful to me than paddling 40 miles down the bay to Churchill. At least I wouldn't have to make small talk with the rocks or explain to the polar bears how, despite the very kind offer, I will have to pass since I'm a vegetarian.

Alan

Alan

- Joined

- Aug 21, 2018

- Messages

- 1,729

- Reaction score

- 1,919

Point taken, Alan. How is Sadie doing? I loved her performance in the Wollaston Lake adventure! A better companion, perhaps than the people we might have met at the lodge. Although it is a Natutalist Lodge. So at least like-minded people. Kathleen and I prefer to paddle alone. We are somewhat introverted, and are not compatible with trippers who like to sing songs, or otherwise encourage group activities. We like the camp to be quiet and still.

We weren't really feeling stress, Odyssey. We just needed to make a decision, and Plan B seemed the most prudent choice. But if you want to see stress, just stay tuned. Will probably post again tomorrow afternoon. I could do so tonight, but people will probably be watching the midterm election returns.

Good Grief Michael, This suspense is killing me! This has been a great trip report, enjoyed every word of it so far. Reminds me of my journey down the James Bay. Now sit down at your computer and cough up the next part of the story! ;-)

dougd

- Joined

- Aug 21, 2018

- Messages

- 1,729

- Reaction score

- 1,919

OK, Doug. I'll do it.

I slept well during the night and was dozing when Kathleen rose just before 9:00 a.m. to go outside. Moments later she yelled out, “Michael. A plane is coming!”

I quickly dressed, rushed up the observation tower, and saw two float planes, flying low, from the south, heading directly toward the lodge. Maybe someone had heard our distress call. These planes must be coming to see us!

As the planes passed overhead we waved excitedly, and the lead plane tipped its wings in response. They continued to fly low, and I kept expecting them to circle back and land. Instead, they simply continued flying north, and were soon out of sight and sound. I guess they thought we were just saying hello. We were at a lodge. There would be no reason for them to assume that we were “stranded.” Moments later, a third plane, with wheels, flew low, just to the west of the Seal River Lodge. It also soon disappeared. We remained alone, with only the wind and the falling tide as company.

We spent our day resting and reading. We also tried more carefully to splice the cable back together with duct tape, but were apparently still unable to transmit, as we received no response. In the afternoon, we went for a tundra hike. When we reached a small lake about 1 km west of the lodge, to collect fresh water, Kathleen spotted a polar bear approaching from Hudson Bay. We walked quickly back to the lodge, climbed the observation tower, and watched the bear enter the tide and swim away toward the south.

We ate our chili supper at 5:00 p.m. and repacked all of our gear just in case a boat should arrive at high tide at 7:25. No luck, however. High tide came, covered the rocks, and then ebbed away, with no boat coming to our aid. Looked like we would spend a second night at the Seal River Lodge. We retired to our beds at 8:00 p.m., for reading, brandy, and fruitcake.We had looked forward to each high tide, hoping that the Seal River Lodge owners would come to open their lodge. But, on our first full day at the lodge, July 18, the morning and evening tides came and left, without any sign of any boats anywhere on Hudson Bay.

On July 19, we woke early to another morning of sunshine and a day of hope that someone would come by boat to the lodge. We were again disappointed when the 7:40 morning high tide left without bringing any boats up from Churchill.

Before lunch, we walked 1 km to the lake to collect drinking water. We spent the afternoon reading, looking at plants, playing cribbage, checking the condition of the polar bear fence that completely encircled our prison/haven, and regularly looking south toward Churchill.

We weren’t fully able to enjoy the area’s beauty, as we thought only of how long it would be before any boat passed by the lodge. Our canoe trip was over. We were at a resort. Yet, we were now dealing with the greatest adversity of the trip. Just like being windbound, we had virtually no control over our destiny. Surely, someone would come by someday to take a message to Churchill for us.

During supper of shepherd’s pie, we discussed our concerns and discomfort. We were warm, dry, had plenty of fuel, food and water, and were in absolutely no danger. Yet we felt uncomfortable. Here we were, living safe and secure in a lodge, doing nothing more than just waiting to be rescued. Somehow, just waiting and hoping seemed wrong. We thought maybe we should try to make a break for Churchill. We quickly agreed, however, that if it was inappropriate to paddle to Churchill 3 days ago, then it was even more inappropriate to paddle to Churchill now, just because we felt trapped. And, we had actually been seen by someone in those float planes. Perhaps they will have returned to Churchill and might mention to Mike, or someone who knows Mike, that “guests” were at his lodge. That might trigger Mike’s memory that he had encouraged us to come to his lodge. Also, we had filed a trip report with the RCMP that indicated we might be at the lodge on these dates. The RCMP might notify Mike. Could we have planned this trip any better? Was our predicament our fault? Had we failed somehow? I didn’t think so.

Our intent (Plan A) had been to assess Hudson Bay before deciding whether or not to paddle to Churchill. We could not, therefore, have pre-arranged for a pickup at the mouth of the Seal River. If we had pre-arranged for a pickup, we could not have paddled to Churchill. Our backup (Plan B) was to paddle to the Seal River Lodge, whose owners told us they open on July 15. They also indicated that we could use the radio phone if no one was at the lodge. I also talked to the owners just before leaving North Vancouver to report that we might arrive between July16 and 19. They said, “Fine. Canoeists often drop by.”

Based on all this planning and preparation, we believed it was reasonable to wait for help, which would surely come someday. Even so, I felt sheepish and to blame for our situation. For the first time on any canoe trip, we were hoping to see boats and people. Also for the first time on any canoe trip, we had seen no one since the pilot left us at Shethanei Lake, nearly three weeks ago.

Twenty minutes before high tide, 8:00 p.m., July 19. No one came.

Reading books in the lodge, we learned of a traditional Inuit saying: “Good luck nearly always follows after misfortune. If this were not so, all the people would die.”

Kathleen and I now waited patiently for our good luck.

Maybe tonight, like last night, we would see the northern lights. Assuming of course that we actually got up during the night. Some of the joy had gone out of this canoe trip.

On July 20, we woke to another sunny, calm morning, and discussed whether we should try to paddle 30 km south to the Dymond Lake Lodge, also run by Mike. Maybe Mike was at the Dymond Lake Lodge. Goofy idea, though. It would likely take us two days to paddle to the Dymond Lake Lodge, and it might also be vacant. Then nobody would know for sure where we were. We could leave a note here, but it was probably safer and wiser to just stay where we were.

Kathleen suggested that we pack up all of our gear to be ready.

“When we first arrived here, Michael, I assumed that the owners of the lodge would come in a day or two. Now I think that they’re probably not coming at all, and that it will only be happenstance that someone might come at a high tide. We need to be ready to leave in a hurry.”

Sounded like a good plan. Besides, it would give us something to do. Something that would make us feel more in control.

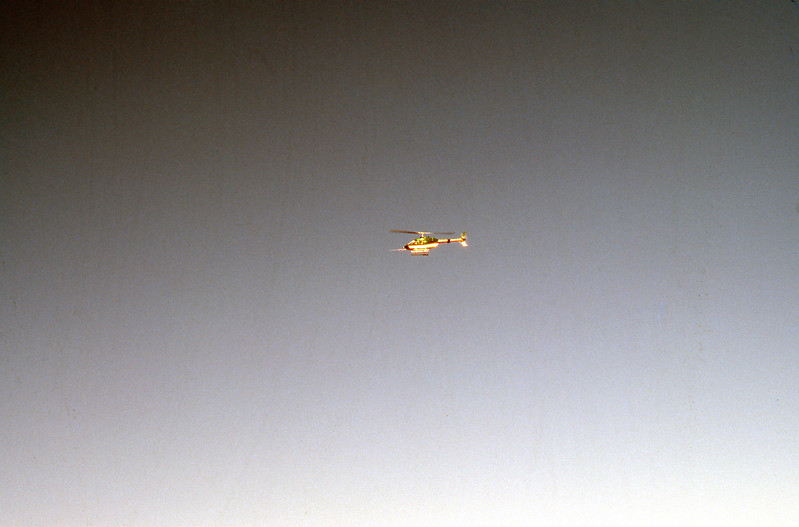

About 8:30 a.m. we left the lodge to walk 1 km to that small lake that you can see in the middle background to collect more drinking water. After reaching only halfway, we heard, then saw a helicopter circling and hovering near the mouth of the Seal River. As it began to fly north, we quickly ran back toward the lodge to intercept its flight path. As we neared the helicopter landing pad, the chopper circled low overhead. We waved wildly, and made downward-sweeping motions, illustrating to the pilot that we would like him to land. The helicopter banked toward us, revealing its markings as a Canadian Coast Guard helicopter. Our hopes soared. Surely they were coming to find us!

The chopper dipped to acknowledge our presence and then sped away rapidly toward the north. Kathleen started to cry. In frustration, I scolded her.

“Be a man, Kathleen. No need to cry.”

I felt embarrassed for myself, for three reasons. First, she can cry if she wants to. The situation seemed to warrant a few tears. Second, “being a man” doesn’t preclude crying. Men cry too. Third, and perhaps most important, I wouldn’t want Kathleen to actually be a man. I liked her very much just the way she was.

Immensely deflated, Kathleen and I returned to the lodge to play cribbage and solitaire.

(I have to post now, as I am getting tired. Don't want to make a mistake, and lose everything I have entered. I can give you a spoiler alert, though. Stop reading now if you don't want to know that we actually did come back alive.)

I slept well during the night and was dozing when Kathleen rose just before 9:00 a.m. to go outside. Moments later she yelled out, “Michael. A plane is coming!”

I quickly dressed, rushed up the observation tower, and saw two float planes, flying low, from the south, heading directly toward the lodge. Maybe someone had heard our distress call. These planes must be coming to see us!

As the planes passed overhead we waved excitedly, and the lead plane tipped its wings in response. They continued to fly low, and I kept expecting them to circle back and land. Instead, they simply continued flying north, and were soon out of sight and sound. I guess they thought we were just saying hello. We were at a lodge. There would be no reason for them to assume that we were “stranded.” Moments later, a third plane, with wheels, flew low, just to the west of the Seal River Lodge. It also soon disappeared. We remained alone, with only the wind and the falling tide as company.

We spent our day resting and reading. We also tried more carefully to splice the cable back together with duct tape, but were apparently still unable to transmit, as we received no response. In the afternoon, we went for a tundra hike. When we reached a small lake about 1 km west of the lodge, to collect fresh water, Kathleen spotted a polar bear approaching from Hudson Bay. We walked quickly back to the lodge, climbed the observation tower, and watched the bear enter the tide and swim away toward the south.

We ate our chili supper at 5:00 p.m. and repacked all of our gear just in case a boat should arrive at high tide at 7:25. No luck, however. High tide came, covered the rocks, and then ebbed away, with no boat coming to our aid. Looked like we would spend a second night at the Seal River Lodge. We retired to our beds at 8:00 p.m., for reading, brandy, and fruitcake.We had looked forward to each high tide, hoping that the Seal River Lodge owners would come to open their lodge. But, on our first full day at the lodge, July 18, the morning and evening tides came and left, without any sign of any boats anywhere on Hudson Bay.

On July 19, we woke early to another morning of sunshine and a day of hope that someone would come by boat to the lodge. We were again disappointed when the 7:40 morning high tide left without bringing any boats up from Churchill.

Before lunch, we walked 1 km to the lake to collect drinking water. We spent the afternoon reading, looking at plants, playing cribbage, checking the condition of the polar bear fence that completely encircled our prison/haven, and regularly looking south toward Churchill.

We weren’t fully able to enjoy the area’s beauty, as we thought only of how long it would be before any boat passed by the lodge. Our canoe trip was over. We were at a resort. Yet, we were now dealing with the greatest adversity of the trip. Just like being windbound, we had virtually no control over our destiny. Surely, someone would come by someday to take a message to Churchill for us.

During supper of shepherd’s pie, we discussed our concerns and discomfort. We were warm, dry, had plenty of fuel, food and water, and were in absolutely no danger. Yet we felt uncomfortable. Here we were, living safe and secure in a lodge, doing nothing more than just waiting to be rescued. Somehow, just waiting and hoping seemed wrong. We thought maybe we should try to make a break for Churchill. We quickly agreed, however, that if it was inappropriate to paddle to Churchill 3 days ago, then it was even more inappropriate to paddle to Churchill now, just because we felt trapped. And, we had actually been seen by someone in those float planes. Perhaps they will have returned to Churchill and might mention to Mike, or someone who knows Mike, that “guests” were at his lodge. That might trigger Mike’s memory that he had encouraged us to come to his lodge. Also, we had filed a trip report with the RCMP that indicated we might be at the lodge on these dates. The RCMP might notify Mike. Could we have planned this trip any better? Was our predicament our fault? Had we failed somehow? I didn’t think so.

Our intent (Plan A) had been to assess Hudson Bay before deciding whether or not to paddle to Churchill. We could not, therefore, have pre-arranged for a pickup at the mouth of the Seal River. If we had pre-arranged for a pickup, we could not have paddled to Churchill. Our backup (Plan B) was to paddle to the Seal River Lodge, whose owners told us they open on July 15. They also indicated that we could use the radio phone if no one was at the lodge. I also talked to the owners just before leaving North Vancouver to report that we might arrive between July16 and 19. They said, “Fine. Canoeists often drop by.”

Based on all this planning and preparation, we believed it was reasonable to wait for help, which would surely come someday. Even so, I felt sheepish and to blame for our situation. For the first time on any canoe trip, we were hoping to see boats and people. Also for the first time on any canoe trip, we had seen no one since the pilot left us at Shethanei Lake, nearly three weeks ago.

Twenty minutes before high tide, 8:00 p.m., July 19. No one came.

Reading books in the lodge, we learned of a traditional Inuit saying: “Good luck nearly always follows after misfortune. If this were not so, all the people would die.”

Kathleen and I now waited patiently for our good luck.

Maybe tonight, like last night, we would see the northern lights. Assuming of course that we actually got up during the night. Some of the joy had gone out of this canoe trip.

On July 20, we woke to another sunny, calm morning, and discussed whether we should try to paddle 30 km south to the Dymond Lake Lodge, also run by Mike. Maybe Mike was at the Dymond Lake Lodge. Goofy idea, though. It would likely take us two days to paddle to the Dymond Lake Lodge, and it might also be vacant. Then nobody would know for sure where we were. We could leave a note here, but it was probably safer and wiser to just stay where we were.

Kathleen suggested that we pack up all of our gear to be ready.

“When we first arrived here, Michael, I assumed that the owners of the lodge would come in a day or two. Now I think that they’re probably not coming at all, and that it will only be happenstance that someone might come at a high tide. We need to be ready to leave in a hurry.”

Sounded like a good plan. Besides, it would give us something to do. Something that would make us feel more in control.

About 8:30 a.m. we left the lodge to walk 1 km to that small lake that you can see in the middle background to collect more drinking water. After reaching only halfway, we heard, then saw a helicopter circling and hovering near the mouth of the Seal River. As it began to fly north, we quickly ran back toward the lodge to intercept its flight path. As we neared the helicopter landing pad, the chopper circled low overhead. We waved wildly, and made downward-sweeping motions, illustrating to the pilot that we would like him to land. The helicopter banked toward us, revealing its markings as a Canadian Coast Guard helicopter. Our hopes soared. Surely they were coming to find us!

The chopper dipped to acknowledge our presence and then sped away rapidly toward the north. Kathleen started to cry. In frustration, I scolded her.

“Be a man, Kathleen. No need to cry.”

I felt embarrassed for myself, for three reasons. First, she can cry if she wants to. The situation seemed to warrant a few tears. Second, “being a man” doesn’t preclude crying. Men cry too. Third, and perhaps most important, I wouldn’t want Kathleen to actually be a man. I liked her very much just the way she was.

Immensely deflated, Kathleen and I returned to the lodge to play cribbage and solitaire.

(I have to post now, as I am getting tired. Don't want to make a mistake, and lose everything I have entered. I can give you a spoiler alert, though. Stop reading now if you don't want to know that we actually did come back alive.)

Last edited:

Excellent, thank you for the effort! This story is like an addiction. Looking forward to the the next part even if it is the end of the tale.

That last entry was one of the best sections of a trip report I've ever read. I was smiling and chuckling the whole time. Looks like you had nice calm sunny weather while you were helplessly waiting around at the lodge. Would have been good weather for paddling to Churchill.

Seriously I would have gone crazy in your situation. I don't like sitting around doing nothing and I don't like to have my situation rest in other people's hands. In your shoes I would have been wishing I'd never been seen by those planes and helicopters. That would have made the decision to start paddling down the bay easier.

I've been telling Sadie about your trip and she doesn't think it sounds so hot. She thinks you should have portaged all those rapids instead of running them. At first she liked the idea of polar bears but when I told her they'd be more likely to eat her than run away (like black bears) she got kind of quiet. Then she asked if I was ever going to take her on another river trip way up north. I told her, no, that I wouldn't.

"Good............What about a lake trip farther south in Canada, one with lots of portages?", she inquired

"Well I'd like to have some river travel too. I don't like just lakes."

"I guess that would be ok. As long as there aren't too many rapids. Could we do another trip that like that sometime?"

"Yes, I think we can. That would be nice."

And then she curled up to go back to sleep while my mind drifted off to thoughts of future canoe trips and how it would have to be in the next year or two before she gets too old to go. My daydreams were interrupted when Sadie, on the edge of sleep, muttered, "And this time find a route with some frogs."

"Ok girl, ok."

Alan

Seriously I would have gone crazy in your situation. I don't like sitting around doing nothing and I don't like to have my situation rest in other people's hands. In your shoes I would have been wishing I'd never been seen by those planes and helicopters. That would have made the decision to start paddling down the bay easier.

I've been telling Sadie about your trip and she doesn't think it sounds so hot. She thinks you should have portaged all those rapids instead of running them. At first she liked the idea of polar bears but when I told her they'd be more likely to eat her than run away (like black bears) she got kind of quiet. Then she asked if I was ever going to take her on another river trip way up north. I told her, no, that I wouldn't.

"Good............What about a lake trip farther south in Canada, one with lots of portages?", she inquired

"Well I'd like to have some river travel too. I don't like just lakes."

"I guess that would be ok. As long as there aren't too many rapids. Could we do another trip that like that sometime?"

"Yes, I think we can. That would be nice."

And then she curled up to go back to sleep while my mind drifted off to thoughts of future canoe trips and how it would have to be in the next year or two before she gets too old to go. My daydreams were interrupted when Sadie, on the edge of sleep, muttered, "And this time find a route with some frogs."

"Ok girl, ok."

Alan

Last edited:

- Joined

- Aug 21, 2018

- Messages

- 1,729

- Reaction score

- 1,919

After lunch, we again set out to the lake for drinking water. We are at the northern limit of trees, and have found this beautiful example of a krummholz tree, whose buds on one side were all killed by the winter blasts. Only those branches insulated by a layer of snow grow and survive. Krummholz is German for "crooked wood."

View back toward the lodge (background on the right) from the watering lake. Every time we had previously gone for water we had seen a polar bear. As you might guess, this made us nervous, and we hoped we would not see one again.

Approximately halfway back, however, and still 500 m from the lodge, Kathleen spotted a polar bear, only 200–300 m (yards ) away. We had read that polar bears never run during the heat of summer. So much the better for us. As best as we could carrying a heavy jug of water and a rifle, we ran to the lodge and scurried through the gate just before the bear reached the fence.

For the next 20 minutes, the bear circled the compound, repeatedly trying to gain entry. We were glad not to be camping in the open. The polar bear is a true predator, and does not run from people. It is actually drawn by curiosity to investigate anything new that it finds.

Looking for a way over the fence.

Looking for a way under the fence.

We had heard before that the Inuit have many names for the polar bear, depending on its age, sex, and reproductive status. And in fact, reading a book in the lodge, we learned that atiqtalaaq refers to a newborn cub. Atiqtaq indicates a cub able to join its mother away from the den. Angujjuaq means a fully grown male. It seems that the broader term for polar bear, Nanuk, has a variety of meanings, including “the ever-wandering one,” “the one who walks on ice,” “the great white one,” and “an animal worthy of great respect.”

We certainly held a great deal of respect for this animal circling our compound, and wondered what the words would be for “polar bear trying to get stranded canoeists inside the fence.” After taking a few pictures of the bear, Kathleen and I climbed the stairs to the observation tower and stood ready, with rifle in hand. If the bear did gain entry and came after us up the stairs, he would be somewhat confined, and I could get more focused shots. I much preferred this strategy compared to the potential chaos of all three of us racing around the compound, with perhaps two of us in panic mode.

The polar bear eventually lost interest, wandered toward Hudson Bay, and lay down in a small tidal pool where it splashed and cooled itself. The bear then continued its journey to the ocean, where it was joined by another polar bear at the water’s edge.

Back in the main part of the lodge, playing cribbage, we again heard the motor of an aircraft. We rushed outside to see a float plane disappearing to the south, likely returning to Churchill.

Back in the lodge to resume our cribbage game, we were quite dejected and wondered how much longer we would remain stranded at the Seal River Lodge. “I think we’re going to have to unpack some of our gear, Kathleen. I’m getting hungry. Maybe we should cook supper. I think we should also get our sleeping bags out. It doesn’t seem like we’ll be going anywhere today.”

Moments later, about 6:00 p.m., we once again heard the unmistakable sound of a helicopter approaching from the north. Again, we rushed outside to see two helicopters flying directly toward the lodge. We ran toward the landing pad, rifle in hand.

Just in case you were wondering, I had rifle in hand for polar bears, not to shoot down the helicopters. We weren’t that desperate yet.

Kathleen and I made very exaggerated motions for the pilots to land. Certainly we must not have looked like normal ecotourists. Certainly we looked somewhat crazed and in need of some assistance. The two helicopters passed overhead, circled around, and then, so very beautifully, landed 100 m (yards) away!

I have been told by a professional writer that the use of exclamation points in modern literature is frowned upon. (Are you frowning right now?) Rather, the content of the words, the strength of the prose itself, should express exclamation. Well, two points about that. First, I am not a professional writer. And second, it was danged exciting when those helicopters landed. Such excitement called for an exclamation point. Modern, professional writers should just be thankful that I didn’t use two or more exclamation points.

We walked up to the pilot and shook hands.

“You got a problem here?”

We blurted out our story. “Open July 15—boarded up—Robertson screws—radio phone—coaxial cable—arctic ground squirrel—four days.”

“Well,” he said, “If you want to go to Churchill, get in. I don’t have room for any gear, though. I can only take you and your wife.”

“Well maybe you should just take Kathleen, then. I should probably stay here and guard the gear. Once she’s in Churchill, Kathleen can arrange for someone to come get me by boat.”

“First of all,” the pilot responded, “I’m going to take both of you or neither of you. Second of all, you tell me you’ve been here for four days and haven’t seen anyone come to the lodge. Who exactly are you guarding your gear from?”

He made a reasonable point. We ran back into the lodge and grabbed our overnight cases. We screwed the plywood shutters back on the side door, jumped into the helicopter, and lifted up over Hudson Bay.

Immediately, nearly 1,000 beluga whales came into view in the shallow water below. (Notice that I didn’t use an exclamation point. I wanted to, though.) Well, maybe we saw only hundreds of beluga whales.But, it could have been a thousand. According to the Canadian Heritage Rivers System brochure, the Seal River Estuary “is the calving and breeding grounds for 3,000 beluga whales.”

Moments later, we approached the Batstone shack at the mouth of the Seal River and noticed how bleak the trip would have been had we tried to paddle to Churchill in 4-hour sprints.

Even near high tide, with the current good weather and wind conditions, the mudflats were extensive and appeared inhospitable for canoeing and camping.

We flew wonderfully and elegantly down the coast, past the still vacant and boarded up Dymond Lake Lodge. And then, only 30 minutes after feeling completely abandoned at the Seal River Lodge, we neared Fort Prince of Wales on the opposite side of the river from the town of Churchill. We landed at the Churchill airport and taxied to the La Perouse House Bed & Breakfast, where we had pre-arranged accommodation for the night of July 20. We had arrived exactly on the day originally planned. (Pencil in an exclamation point at the end of that last sentence if you wish. In fact, I encourage it. Modern, professional writers be danged, I exclaim!)

We knocked on the door and were welcomed in by our host, a very gracious woman. “I’m glad to see you,” she said. “I mentioned to my son, who works for the Department of Natural Resources, that I was expecting guests this afternoon.”

Apparently this news perplexed her son, as it’s not easy to get to Churchill. There are no roads to Churchill. And, if I remember correctly, the train arrived only three days per week. Similarly, only a limited number of commercial flights served Churchill on any given day. Her son was probably thinking that on a late Sunday afternoon, everyone who was going to be in Churchill was already in Churchill.

“How are they getting here?” the son asked his mother. (I apologize for not remembering their names.)

“They’re canoeing down from the Seal River.”

And her son’s response? You guessed it. “They can’t do that. They’ll die.”

“I was getting worried about you,” she told us. “I’m glad that you made it.”

“We are very glad to be here.”

We told her about our four days at the Seal River Lodge, and the helicopters, and how we had to leave all our gear behind, including clean clothes.

“That’s OK,” she said. “Take those dirty clothes off. I’ll put some bathrobes in your room. While you’re showering, I’ll put your clothes in the washer and dryer.”

Yep. Kathleen and I were very glad to be at the La Perouse House Bed & Breakfast.

Two hours later, Kathleen and I sauntered to the restaurant. We marvelled at how quickly our situation had changed. At 6:00 p.m. we were stuck in the lodge, seemingly forever. By 9:30 we were strolling casually to the pub for hamburgers and fries.

We sat down and asked the waitress to bring us a beer. Didn’t make any difference what kind of beer. Just bring us a beer. “And we would also like some French fries and a cheeseburger. Lots of gravy on those fries, please.”

A few minutes later, our rescue helicopter pilots sat down at the next table. “I’m glad you saw us,” I said. “No telling how much longer we would have been at the lodge if you hadn’t seen us.”

“Well, we didn’t see you at all. Unless you’re looking for people on the ground, you almost never seem them. We turned back only because we wanted a closer look at the lodge.”

Dang. That was lucky for us. “You know,” I continued, “We had an EPIRB with us, but we never considered using it, even for a second. Just out of curiosity, if we had set the EPIRB off, would we have been charged? How much would it have been?”

“Well, for almost all rescues, there is no charge. Your situation was different though. You were at a lodge. You weren’t hurt. You weren’t sick. You probably had a month’s supply of food in the pantry. If you had set the EPIRB off, it would have been only because you were tired of being there and wanted to go home. They might not have charged you, but it could have been as much as $20,000.”

Well, as I said, we never considered using the EPIRB. It would have been too embarrassing. I would have to be pretty much already dead before I would set it off. We ordered another beer. Life was again beautiful. Plan C, hitching a ride on a helicopter to Churchill, worked to perfection.

(Special note to Mike McCrea: I know that you are interested in gear. What works. What doesn't work. After this trip we started carrying red emergency flares that can be launched from our bear banger. People in planes would more likely see us. Haven't had a chance to test the theory yet, though.)

Last night, while Kathleen was in the shower, I called Mike. I didn’t write down the conversation in my diary, so the following is what I remember 17 years later. The gist of the conversation, I believe, is accurate.

“Hello Mike. This is Mike from Vancouver. I talked to you about a month ago, about my wife and I canoeing down the Seal River, and our plan to paddle all the way to Churchill. Do you remember?”

“Yeah.”

“You told us that it was too dangerous to paddle to Churchill, and that we should come up to the Seal River Lodge, which would be open on July 15. Remember that?”

“Yeah.”

“Well, we arrived on July 17, but no one was there.”

“We decided not to open on July 15.”

“You said if no one was there, that we should use the radio phone to call, but it didn’t work. The cable had been severed. Anyway, Mike, some helicopter guys brought us back to Churchill this afternoon, but our canoe and all our gear are still back up at your lodge. Can we hire you tomorrow to take us back up there to retrieve all our stuff?”

“I don’t have time.”

It was a friendly conversation, even though unproductive from my point of view. Some people have suggested that I should have been angry with Mike, but I wasn’t at all. We were not Mike’s responsibility. As far as he knew, we might have changed our minds about paddling the Seal River. As far as he knew, we might have paddled to Churchill. After all, that’s what we told him we were going to do. Mike had a business to run. It wasn’t his job to interrupt his work to go up to the Seal River Lodge on the off chance that Kathleen and I might be there.

Anyway, after talking to Mike, I called Jack Batstone. “Hello Jack. My name is Mike. My wife and I paddled down the Seal River and arrived at the Seal River Lodge on July 17, expecting that Mike and his guests would be there. It was still boarded up from the winter, though. Some helicopter guys saw us there and have brought us to Churchill. But our canoe and all our gear are still back up at the lodge. We were hoping that we could hire you tomorrow to take us back up there on your barge to get all our stuff.”

“I don’t know if I want to go up there tomorrow. I’d have to find out when high tide is.”

“Jack, I’ve been staring at the tide tables for four days. Tomorrow morning’s high tide is at 9:20.”

“OK. I’ll pick you up at eight o’clock tomorrow morning. My cost is $250.00.”

I already knew about Jack’s cost. Two-hundred-and fifty dollars was his advertised price per canoe for picking people up at the mouth of the Seal River.

Jack showed up exactly at eight. We climbed into the truck. Jack looked at us and said, somewhat sternly, “You better bring a coat. It’s going to be cold and wet out there.”

“I told you, Jack. All our gear is at the lodge. These are the only clothes we have.”

Jack grumbled. When we boarded his high-bowed barge, he handed us some rain gear. Jack was right. The trip across Hudson Bay to the lodge was cold and wet.

We arrived at the lodge at 9:35, 15 minutes after high tide. “I’m going to set you on shore,” Jack said. “I can’t tie up. The tide’s going out. You’ll have to canoe back out to me. I hope you don’t take very long to get back here.”

“It won’t take long at all, Jack. Our stuff is already all packed up.”

I removed the Robertson screws from the plywood shutter on the side door. Fifteen minutes later, all of our gear was at the water’s edge. I screwed the shutter back on the side door. We loaded the canoe and paddled out to Jack, who helped us transfer canoe and packs onto his barge. Only 10:00 a.m., and we were heading back to Churchill.

About halfway across the bay, Jack said, “You know, $250.00 is what I normally charge for each canoe when I pick people up. Usually I pick up at least three canoes on each trip. But you’re only one canoe.”

“You should charge what you think is fair, Jack.”

Jack thought for a moment, and then continued. “You know, I had to miss a half day of work this morning.”

“Be fair to yourself, Jack. Charge what you think is fair.”

Back in town, Jack swung by the train station. “We’ll leave your canoe here,” he said. “No reason to take it to the B & B just to bring it back again.”

“But what if someone steals it, Jack?”

“Who’s gonna steal it? There’s no way to get a canoe out of town except by train. Everyone would see them. No one’s gonna steal your canoe.”

At 11:45, Jack dropped us off at the La Perouse House Bed & Breakfast.

“You know,” he said, “To put you on shore at the lodge, I damaged my propeller on the rocks. Normally I don’t get anywhere close to shore when I’m picking up canoeists. They always paddle out to me. I think $250.00 is too low a price.”

“Jack. I understand. Just tell us what you think is a fair price.”

“I think another $50.00 would be fair.”

“We were thinking more like an extra $100.00, Jack.”

Jack seemed pleased. I would have paid even more if Jack had asked. He had helped us out of a very difficult situation, and we very much appreciated his efforts.

So, by noon we were back in Churchill to become tourists as we headed out on the road to Fort Prince of Wales.

The men who lived at the fort worked as clerks, tradesmen, and administrators for the Hudson Bay Company. Company journals and reports indicate that alcoholism was a major problem. I’m sure that there wasn’t much else to do during those long, lonely, boring, bleak winters on the frozen shores of Hudson Bay.

Forty cannons were placed to protect the fort from attack. According to the tour guide, 10 men were needed to operate each cannon. But only 39 men lived at Fort Prince of Wales in 1782 when a French naval force under the leadership of de La Perouse besieged the fort. Samuel Hearne surrendered without firing a single shot in defence. I don’t know why I’m telling you this. It just seemed such an ignominious defeat for what had been the largest fort in North America.

After breakfast, Kathleen and I wandered over to the train station. My canoe was still there. I know Jack told me that no one would steal it. I just wanted to be sure. We hired a guide, who boated us over to Sloop Clove, where we viewed Samuel Hearne’s signature, which was carved into the rock in 1767. I still admired Samuel Hearne despite his quick surrender to de La Perouse. There was little else that Hearne could have done, however. According to Farley Mowat, in his book Tundra, “The French had four hundred men, and Hearne had thirty-nine. The uncompleted fort was, as La Perouse noted, indefensible, and Hearne had no choice but to surrender.”

The Hudson Bay Company used Sloop Cove to secure their boats safely from the ice during winter. Because of the rebounding land, however, Sloop Cove is now high and dry, less than 250 years later. On our return back across the river, we boated among hundreds of beluga whales, who swam right up to the edge of the boat to let us pat them on the head. You should have been there. It was so overwhelmingly cute.

Kathleen and I boarded the train for Thompson, Manitoba at 11:00 p.m. At the station, we met Brian and Penny, from Winnipeg, who had just finished paddling the Thlewiaza River, which enters Hudson Bay 150 km north of the Seal River. We settled into our seats and chatted away about our respective adventures. Brian and Penny were kindred canoeing spirits—our Plans A, B, and ultimately C seemed to resonate very well with them.

Just before noon, our overnight train pulled into Thompson, Manitoba. I taxied out to the airport parking lot to get our van. The side-view mirror had been fixed, just as La Ronge Air had promised. Back at the train depot, Kathleen and I loaded the van, drove into town for lunch, and then headed west, back toward Vancouver.

You might know of a famous quote by Pierre Elliot Trudeau, a canoeist and former Prime Minister of Canada:

"What sets a canoeing expedition apart is that it purifies you more rapidly and inescapably than any other. For it is a condition of such a trip that you entrust yourself, stripped of your worldly goods, to nature… (and) throughout this time your mind…learn(s) to exercise itself in the working conditions (that) nature intended….Indeed, paddle only a hundred in a canoe and you are already a child of nature."

Canoe at lunch, at the confluence of the Seal and Wolverine Rivers.

You might be thinking that our Seal River adventure was now over. But for me, it will always remain unfinished. As Alan Gage observed in a previous post, those 4 days at the Seal River Lodge were calm and sunny. We could have made it to Churchill in 4-hour sprints. Even as I write these words 21 years later, I regret that we hadn’t at least tried. It would have been so danged exciting to paddle into Churchill, when everyone said we couldn't do it.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 147

- Views

- 17K

- Replies

- 11

- Views

- 737

- Replies

- 63

- Views

- 6K