Friday, June 28. Still calm the next morning. I placed our new grate across the rocks of an existing fire pit to cook my morning bannock. The grate was much higher off the ground than I was used to, and I made a larger fire than normal. Big mistake. The fire was way too hot, and burned the bannock. I should have just cooked our bannock the normal way. I should have scratched out a shallow pit on the beach. But I was trying to save time. Don’t know why. We had pretty much unlimited time. Good to know that I’m not perfect.

Kathleen and I arrived at Lower Laberge, at the outlet of Lake Laberge, in about an hour. We enjoyed reading about, and strolling through the history of the Thirty Mile River. Dense bush covered the site, which was quite buggy. Also, no firewood. We had made the right choice yesterday to camp near the end of Lake Laberge.

Kathleen at the plaque commemorating the Thirty Mile River as a Canadian Heritage River.

Old cabin at Lower Laberge.

Old truck at Lower Laberge.

After a fairly short visit at Lower Laberge, we headed down the Thirty Mile River, which featured many boils, whirlpools and some riffles. I doubted that the German-With-A-Dream could have paddled this successfully. Tyrell Bend would have been particularly challenging for him. I wondered about what kind of screening process outfitters might use to determine if potential clients like the German had the skills and background to paddle from Whitehorse to Carmacks.

Not our problem, I suppose. Anyway, Kathleen and I had a very enjoyable day of running swift Class I water. We reached Hootalinqua (

https://sightsandsites.ca/rivers/site/hootalinqua), the end of the Thirty Mile River, about four o’clock. Two canoes and one kayak belonging to five women had just arrived down the Teslin river, which joins the Yukon here at Hootalinqua. We toured around the historical site, which, like Lower Laberge, did not appeal to us. Dense and buggy. We quickly decided not to stay.

We beached our canoe at Hootalinqua around four o’clock.

Covered eating area at Hootalinqua, with trail leading to outhouse.

Old cabin, old me and new interpretive sign at Hootalinqua

History of Hootalinqua telegraph station.

History of Hootalinqua village.

We climbed back into the canoe, and paddled down a few minutes to Shipyard Island, which, according to Rourke, had a “Good Camp.” Rourke didn’t say whether the good camp was at the top or bottom of the island, or on which side of the island. We paddled to the outside of the island, and were sceptical that good camping existed. The island seemed overgrown, and was probably buggy. We paddled slowly, though, and saw what appeared to be an opening, perhaps even a trail into the bush. We stopped, and got out to investigate. We were almost stunned to see an old ship, the steamer

Evelyn.

I suppose we shouldn’t have been surprised. After all, the island was named Shipyard (

https://sightsandsites.ca/rivers/sit...alinqua-island). And, there was also a picture of the

Evelyn in Rourke’s guide book. Nevertheless, we were stunned.

Although Kathleen said the ship was spooky, we set up camp. Rourke indicates that the

Evelyn was built in Seattle in 1908, which has been resting here since around 1913. For supper, Kathleen and I enjoyed our usual Friday fare of tuna casserole. Afterwards, Kathleen poured two ounces each of brandy, “In celebration of being on moving water.” We retired to the tent early.

The steamer

Evelyn on Shipyard Island.

Very spooky, indeed.

Our camp on Shipyard Island.

Saturday, June 29. Up early, around six-thirty. Cooked our morning bannock on the Coleman Peak 1 back-up stove, which turned out much better than yesterday. I had redeemed myself by serving Kathleen a golden-brown, unburned, canoe-trip breakfast tradition.

As we were beginning to pack up, a power boat passed by only a few metres (yards) off shore. The boat returned only moments later, and four young men straggled onto shore. They had seen the apparent trail into the bush, and, like us yesterday, stopped to investigate. They liked what they saw, and decided to stay for breakfast.

The apparent leader of the group, after all, it was his boat, attempted to move the existing metal fire pit down to the beach. He gave up when he realized the fire pit had been anchored to the ground, probably by the Yukon Government. He looked around for some firewood. I pointed out that Kathleen and I had not been able to find any firewood.

“No problem,” he said, and he headed back to his boat. He returned moments later with a battery-operated chain saw, and headed off into the bush. He returned a few minutes later, dragging a live spruce tree that he then cut into bolts and split into fairly large pieces. He placed several of them, along with some kindling, in the fire pit. He lit the kindling, and stood back quite satisfied. As you might guess, the fire sputtered and went out.

He returned to the boat, and brought back a jerry can, which he shook over the fire pit. Lit the kindling again, and stood back quite satisfied. As you might guess, the fire sputtered and went out. After all, the wood was green.

Never one to give up, he lit the fire again, held the jerry can over the fire, and poured gas on the flame. He kept this up until the flame ran up the pouring river of gas and ignited the jerry can spout.

“You better put the can down. It might explode,” I said. Kathleen, I and his three companions were all a bit wide-eyed. The guy holding the jerry can seemed unperturbed, however. After watching the flame for a few seconds, he pressed the jerry can spout against the arm of his sweatshirt, which extinguished the flame. Too bad Kathleen didn’t have her camera out. The episode would have provided some great images.

The flaming-jerry-can-guy also had brought along his dog, Olaf. We chatted a bit about dogs, and our concern for Shadow back in the Tails and Trails Dog Hotel. “We hope he’s all right,” I said. “He’s afraid of everybody and everything new.”

Flaming-jerry-can-guy opined that Shadow had probably been abused, suggesting that “Dogs are not born timid.” I liked flaming-jerry-can-guy a lot better, now that he had shown empathy for Shadow.

Kathleen and I finished packing up, and prepared to leave. Kathleen visited the outhouse one last time. When she returned to the beach, she said, “Good thing we’re leaving now, Michael. I think they’re planning to have a party. They’re cooking up bacon and eggs, drinkin’ beer and smokin’ marijuana.

A couple of hours later, we approached “Klondike Bend,” where Rourke says the hull of the steamer

Klondike #1, built in 1929, can be seen at low water. We paddled to the inside bend to have a closer look. In 1936, with an inexperienced pilot at the wheel, the ship failed to make a bend in the river, and smashed into rocky cliffs at km 154.5 (mile 95),

Approaching “Klondike Bend”

before coming to rest here at approximately km 196 (mile 121).

The day was dry and warm, and we drifted leisurely downriver, stopping for lunch on a narrow beach in “Glacier Gulch Bend.” Rourke suggested that this spot provided a “Potential Camp,” but we considered it too overgrown. Besides we weren’t ready to camp yet. As we were packing up, two paddlers with double blades drifted by in solo rafts.

Lunch on a narrow, gravel beach in “Glacier Gulch Bend”

We also soon drifted on, noting the landmarks detailed in Rourke’s guidebook. “Big Eddy Woodcamp,” where an Eagle sat unflinching at the top of a spruce tree despite being harassed by a pair of swooping and diving Ravens. Then “Upper Cassiar Bar,” which begins a stretch of the river where gold was discovered in 1886. A party of four men was reported to have taken out $6,000.00 in only thirty days.

View toward Big Eddy Woodcamp.

View toward “Upper Cassiar Bar”

Just before the Big Salmon River, we pulled out on river right to inspect a spot that Rourke listed as “Good Camp,” with “Cabin Good Condition.” It was more than a good

camp—it was a great camp. It also featured an outhouse? Although early in the day, a little before three o’clock, we decided to stay, and relaxed on shore, watching the Yukon River roll on by.

As we were setting up, we saw four tandem canoes approaching. I stood on the bank, making myself very visible, hoping they would stop. The Yukon River is very popular. We expected to see people everyday. We were actually looking forward to meeting other paddlers. Looking forward to sharing stories, not only of the Yukon River, but also of previous wilderness adventures.

The first two boats paddled by without even slowing down. Two bad. It would have been nice to have visitors for at least an afternoon. Suddenly, the bowsman in the lead boat yelled out, “Do you mind if we camp behind?”

Kathleen relaxing on shore, watching the Yukon River roll on by.

“Not at all. It’s a large camp. Plenty of room for everybody. We would enjoy the company.”The two leading canoes worked hard to paddle back up against the current, but eventually all eight of our visitors stood on the beach. The bowsman in the first boat introduced himself.

“I’m Rainer Russmann, I’m the owner of Yukon Wild, and I’m leading this group on a guided canoe trip. We had been intending to camp here, as it’s great camp. But when I saw you, I thought that we shouldn’t. My policy is to never bring one of my larger groups into a camp that’s already occupied by only a small group. But it’s such a great camp, and my people had been looking forward to stopping. I hope that you really don’t mind.”

“Not at all,” I said. “We’re glad you stopped. I was just getting ready to carry my canoe higher up the bank above the river. Do you think you could give me a hand?"

“Use me,” Rainer said, as he and another guy grabbed my canoe and carried it up the bank.

Can you guess which one of the people in the image below is Rainer, the guide? Pretty obvious, isn’t it? Rainer’s group included four Germans, one Swiss and two Englishmen. They had begun their trip at Johnson’s crossing, on the Teslin River. From there, they paddled 185 km (115 miles) down the Teslin River to its confluence with the Yukon River at Hootalinqua. Many groups select this route to avoid the much-ballyhooed terrors of Lake Laberge. They planned to end their trip at Carmacks.

We asked Rainer about his industry’s approach to people like the German-With-A-Dream. “What do you do when people come to you, wanting to rent a canoe, and head off by themselves down the Yukon River? Do you try to assess their skills?”

“No. It’s like if someone shows up to a car rental place with a driver’s license, and wants to rent a really hot car, you rent it to him. I wouldn’t ask him if he can handle such a car. It’s his own fault for not being aware of his limitations. I have no sympathy for him. It was his choice.”

Rainer, seated far right, and his guided trip, just before the Big Salmon River

Kathleen and I also wondered if they had seen the flaming-jerry-can-guy. We hadn’t seen them all day. They had a power boat, and should have caught us by now.

“Well, we heard them at Shipyard Island. Music blaring away. We didn’t stop.”

As you might have anticipated, I also asked Rainer about Five Finger Rapids. He said, “Just stay right.” We chatted about some of our other wilderness trips. Rainer, Kathleen and I had all done the South Nahanni River.

“Where’d you put in, Rainer?”

“At Rabbitkettle Lake. We didn’t have enough time to start at the top, at the Moose Ponds.”

“When Kathleen and I did the Nahanni with two other couples, we started at the Moose Ponds. We scouted the first rapid in the Rock Gardens, but then just ran down the rest of them.”

Rainer’s eyes actually got big. “You ran the Rock Gardens, and you’re worried about Five Finger Rapids? You should be leading trips through Five Finger Rapids.”

Maybe, I thought to myself. But I’m a lot older now. I’ll be 72 in a couple of months. And Five Finger Rapids has a name. You always gotta worry about rapids that have a name. The Rock Gardens had a name, and they were quite challenging. (Note: For those of you who might not know, the Rock Gardens are two-and-a-half days of essentially continuous whitewater, with rapids up to Class IV.)

“Our favourite trip, Rainer, was the Thelon River in 1993. Just Kathleen and me. Thirty-seven days and 950 km (590 miles) from Lynx Lake to Baker Lake. We loved the Barren Grounds.”

Rainer’s eyes got big again. “I’ve always wanted to do the Thelon. But I don’t think I’ll ever have enough time.”

I contemplated telling Rainer that Kathleen and I had self-published a book about our Thelon River trip. A compilation of our diaries. But I never like to promote myself. I should have mentioned something. He might have enjoyed our book.

There was no firewood around our well-used camp, but Rainer brought a small handsaw. His group scurried about, and soon had a fire going, which we used to cook our quesadilla. Rainer pretty much did all the work preparing his group’s supper. Maybe Kathleen and I should consider booking a guided trip next summer. It’s so expensive, though. Maybe I’m not quite lazy or old enough yet. And besides, what if I didn’t get along with the rest of the group? Sometimes I’m not all that likeable myself.

Except for that first day on Lake Laberge, we had generally enjoyed warm, calm sunny, worry-free weather. But forest fires were burning out there somewhere. As Kathleen and I prepared for bed around ten o’clock, smoke began to fill the Yukon River valley.

Me and Kathleen lazing about, watching Rainer do all the work.

Preparing for bed, just before ten o'clock.

Smoke from forest fires begins to fill the Yukon River valley.

Sunday, June 30. I slept until seven-thirty. Ash from the forest fires had coated our tent fly overnight. Rainer already had the fire going, and I used it to heat tea water for Kathleen and me. Pretty nice to have someone like Rainer doing all the work.

Rainer’s group soon began to cluster around the fire to toast bread on the grate. There was no room to cook my bannock. Rainer noticed the bannock mixture in my pan.

“Would you like more space on the fire?”

“I can wait, Rainer, It’s your fire.”

“No. It’s

our fire,” he said.” With that, Rainer rearranged the toasting bread to give me enough room to cook our traditional morning bannock.

One of the Englishmen in Rainer’s group had been working for a media company in Hong Kong for five years,. He said that “I’ve always heard that Canadians love bannock, and finally I get to see how it’s done.”

The whole group gathered around to watch me cook our morning bannock. Lots of audience pressure on me, but I was up to the task. Our bannock came out golden brown on both sides. The audience didn’t cheer or clap after my performance, but I think they should have.

If you look back at the image of Rainer’s group, you will note the lady on the left, and her husband seated to her left. After ending their trip at Carmacks, this German couple intended to head back to Whitehorse. From there, they planned to rent a canoe from Rainer, and paddle by themselves down to Dawson City. “We have to do the whole thing, don’t we? ” she asked. I agreed. You gotta do the whole thing.

I must point out, however, that the Yukon River is the third longest river in North America, flowing 3,190 km (1,980) miles from its source in British Columbia to the Bering Sea in Alaska. The 715 km (443 miles) between Whitehorse Dawson City can not truly be considered the “whole thing.” Most people, though, associate the Yukon River with the history of the 1898 Klondike gold rush, which occurred primarily between Whitehorse and Dawson City. From that perspective, the stretch from Whitehorse to Dawson City constitutes the “whole thing.” (Note: Some references consider the Mackenzie River to be longer, depending on where one decides the Mackenzie actually begins.)

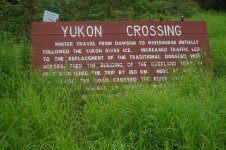

Reminders of the history of the Klondike gold rush were common throughout our trip. This sign stood immediately across the river from our shared camp with Rainer’s group. It reads:

This N.W.M.P. detachment, named for the nearby Big Salmon River, was one of several established in 1898 at 50 to 65 km along the Yukon River. From the Chilcoot Pass to Dawson City, the “Mounties” kept order and assisted 30,000 Klondike gold-seekers. The telegraph station built in 1890 still stands. But little is left of the police post, which closed in 1901. The sign is severely out of date, however, as Rourke indicates that a 1995 wildfire completely destroyed the telegraph office.

Big Salmon Northwest Mounted Police Post

Kathleen and I prepared to put on the water a little before ten. I was disappointed to discover that the bow bungee cord had been snapped in two. Must have happened when Rainer and another guy in his group moved my canoe higher up the bank for me. Some people don’t really know how to pick up canoes. You’re supposed to use the thwart or grab loop, not the bungee cord. Not a big deal, though. I simply tied it back together. Still, it would have been nice if the person wanting to help me had just mentioned the accident.

About 15 years ago, at the beginning of a weekend trip with a new group, I was about to throw my canoe up onto my shoulders to carry it to the water. Suddenly, without asking, a guy rushed over to help. He picked up the canoe, not by the thwart or grab loop, but by the wooden deck, which immediately cracked. He looked at me, but didn’t say a thing. Probably thought I wouldn’t notice. These are the only two times that strangers have ever helped me move my canoe, and both times damage resulted. Might be an obvious moral to this story.

Morning camp after breakfast. Russ Giesbrecht, an active trapper, maintains this “Cabin Good Condition.”

Anyway, Kathleen and I laced up the spray deck, and headed downriver, intending to reach the Mandanna Creek campground, about 70 km (45 miles) away, just north of the Little Salmon River. Both Rainer and Rourke recommended it as a “Good Camp.”

About two hours later we stopped for a pleasant chat with the two solo rafters that we had seen during yesterday’s lunch break. A German guy living in Vancouver with his Russian girlfriend. He said he had never met anyone before from Saskatchewan while paddling on northern Canadian rivers. As it turns out, neither had we. In fact, nearly all of the other paddlers that Kathleen and I had ever seen on wilderness trips were non-Canadian, most often German. We mentioned that Rainer was German, with two Englishmen, four Germans and one young Swiss woman in his group.

“Did she speak German?” he asked.

“I think so.”

“Well, they might not agree, but if you speak German, you’re German.”

Don’t know what that means, really. Don’t even know how to analyze it.

A few minutes after putting back on the water, a strong north wind sprang up to blow directly at us. Whitecaps on the river. No fun at all. Very hard work. The calmest conditions were on the inside bends, but the fastest current was on the outside bends. I tried to select a route that optimized the trade off between these two choices. I thought of The German-With-A-Dream, who had paddled only on lakes, and had heard that the Yukon had no rapids. I don’t think he could have handled this solo, with his limited skills. Hell! We were having a tough time. Kathleen seemed frustrated

“I never expected to have to paddle hard for two weeks, and 700 km (435 miles). to Dawson City.” (Note: Kathleen didn’t actually refer to the miles in her statement. I put that in there for those of you who might prefer imperial units.)

Indeed, we had both expected a leisurely float to Dawson City. I had told yellowcanoe that we planned 15 days to reach Dawson City from Whitehorse. She said that it would take us 15 days if we did a lot of back paddling. This was not what I was expecting when I was saving the Yukon for when I got old. This is not what I expected when yellowcanoe wrote that the Yukon is a seniors’ river.

Well, you get what you get, and we got even more wind. After lunch, a strong gust blew my Tilley hat off. I had forgotten to reset the chin strap. As you might know, Tilley hats float because of a little piece of foam inserted into a sleeve. We chased the hat downriver, bracing against conflicting currents and winds, and finally caught it. A near catastrophe. I gotta have my Tilley hat. I’m bald, and burn easily. I do always take a spare baseball cap just in case, but it’s not as protective as my Tilley hat.

Just before the confluence with the Little Salmon River, we were ferrying over to river right. Strong current pushed us downriver. Strong wind pushed us back up. I felt vulnerable in the middle of the wide Yukon River. I yelled out to Kathleen. “I hate this.” I should have said so sooner. Ten minutes later the wind subsided.

Rourke’s book has been fantastic. Lots of historical information, plus indications of good campsite locations. Compared to most of our previous wilderness trips, Kathleen and I considered the camping in this section of the river to be poor. Bush right down to the river. Limited gravel bars. Very little driftwood. Rourke’s book is a must for this stretch of the Yukon River.

We reached Mandanna Creek camp at six-thirty. Pretty good considering all the headwind. We enjoyed a gorp snack on the beach before setting up camp. At 8:00 p.m., a solo kayak and a tandem canoe from the Up North outfitters paddled by, enveloped in smoke. They didn’t slow down. Maybe they intended to reach Coal Mine Campground, only about 40 km (25 miles) away for burgers and booze tonight. Kathleen poured two ounces of brandy for our pre-supper celebration. So far, the Yukon River had not been a “float.” Maybe soon. After brandy, we dined on smokies and beans for supper.

Smoke now filled the Yukon River valley. We wondered how close the forest fires might be.

Smoke from forest fires filled the valley at Mandanna Creek camp.