Thanks for the offer to walk our dog, Mihun09. The roads must be bad, 'cause you're not here yet. But the coffee is on! And thank you, Gamma1214, for a least determining how far you would have to come!

--------------------------------------------

END OF INTERMISSION

-------------------------------------------

I sat upright until 2:00 am, just to be ready to grab the tent should it come apart. At 2:30 am the wind no longer hurled snow and I felt slightly more confident that the tent would survive the onslaught. By 3:00 am the wind stopped, and we were surrounded by beautiful silence, broken only by the soft, frog-like clucking of a Willow Ptarmigan that had sought refuge in the immediate lee of our tent. Truly extraordinary that the ptarmigan had found us way out here. I fell into a restless sleep.

I awoke at 8:00 am to a calm, but heavily overcast morning, warm at +3 degrees. On the windward side of the tent, snow that had been hardened by the gale had accumulated halfway up the tent, blocking our front door egress. We kicked our way out to a gloomy morning. All our gear, including the sled, lay buried beneath the snow. The packed ski-doo trail had been completely obliterated. We ate a quick breakfast of dry granola and packed up.

We still couldn’t see any shoreline, and were not exactly sure of our position. Based on how long we had travelled yesterday, I estimated that we had covered 26 to 28 km (16 to 17 miles), which put us 12 to 14 km (7.5 to 8.5 miles) from town. Assuming we could still travel at 3 km/hr (1.8 miles/hr), we should reach town in 4 to 5 hours, by early afternoon.

We leaned into our towlines and headed down the ski-doo trail, which disappeared in only a few steps. We floundered about looking for it, continually breaking through the wind-hardened crust. After only a few frustrating minutes of unsuccessful searching we unpacked and put on our snowshoes. These conditions would certainly make for a longer day.

The wind resumed its attack at mid-morning, creating white-out conditions. Our world had shrunk to a very small realm, often 200 m (yards) in diameter or less. We travelled by ‘dead reckoning,’ which is a navigational process of estimating one's current position based upon a previously determined position, and advancing that position based upon known speed, elapsed time and course. I was pretty sure of our position last night, and had set my compass to 208 degrees, to a point around which lay the town of Colville Lake, perhaps now only 10 to 12 km (6 to 7.5 miles) away. We just needed to be able to walk in a straight line at 2 km/hr (1.2 miles) for 5 to 6 hours, and we should be there by mid-afternoon. Of course, it’s not possible to walk in a straight line for 10 km (6 mils) when one can’t see fixed points up ahead. I hope that the term ‘dead reckoning’ didn’t actually arise because people ‘reckoned they were dead.’ Just a joke. With patience I’m sure we’ll make it. We’re bound to touch shore somewhere, eventually. Even if we don’t reach shore today, we can always spend another night out on the lake.

As the day wore on, the temperature rose above zero (32 F), which made the snow slushy, with poor dragging conditions. Our pace slowed. The slush froze to our lamp wick snowshoe bindings, which eventually frayed and tore away completely. We were forced to stop to make four new bindings. Weaving the new bindings into our snowshoes required that I remove my mitts to be able to use my fingers. I had to stop several times to re-warm my hands, and the process took over 30 minutes. Still, though, there’s no deadline for when we have to reach town. We’ll get there eventually. I held out the compass. We leaned into our towlines and continued heading 208 degrees into a wind that refused to leave us alone.

The ice now became quite jumbled, with large fields of blocks and pressure ridges more than a metre high. The Conover book,

A Snow Walker's Companion, had warned us about pressure ridges on large lakes. When the ice had formed last fall, it had also expanded. Since the edges of Colville Lake are immovable, the expanding ice developed stress cracks that rose up – just like mountains rise up above colliding tectonic plates. Sometimes, during very cold weather early in the winter, these stress cracks can separate and expose open water that might refreeze beneath thin ice intermixed with deeper ice. Within these jumbles of pressure ridges there is often no way to tell where the ice is thick, and where the ice is too thin to support a person’s weight.

For an hour we worked our way cautiously through the maze, poking at and testing the ice as we pulled and pushed our loads up and down the ridges. This was very hard work. Not at all like the euphoria that we had hoped for. It was an adventure, though, and I was glad for the experience.

Finally we reached smooth ice, and stopped to rest. We hadn’t covered much distance in the last hour or two, and we certainly hadn’t been going in a straight line through the pressure ridges. No telling how far we were from town. No telling in what direction town lay. On the other hand, pressure ridges often form around islands that offer resistance to the expanding ice. The topographic map shows an island more than 1 km (0.6 miles) long only 2 to 3 km (1.2 to 1.8 miles) from the cape toward which we have been heading. Maybe we’re by that island. Maybe it’s not too far to go now. We’ll just have to press ahead and hope for the best. We hope it’s not too much farther. We’re getting a bit tired.

Thirty minutes later the wind began to subside, the weather cleared a bit, and the shoreline came into view. Wow! We’re almost there. We seem to be right on track.

The town of Colville Lake sits in a cove behind a cape, and can not be seen by travellers approaching from the north and east of the cape. Bern had mentioned that we would see no sign of Colville Lake until we were close enough to see the windsock at the airport, which sits on a hill above the town.

We stopped, and gazed toward the shore through our binoculars. Yes, there it was! The windsock, like a beacon, stretched out in a line directly toward us. With renewed energy we leaned into our towlines. We dragged on for what seemed like hours without getting any closer. We were obviously getting very tired and impatient now that the goal was so near. About 1 km (0.6 miles) from town we saw Margaret and Jo-Ellen, out running Margaret’s dogs. They roared over on their ski-doos and offered to drag us and our loads up into town.

“No, thanks. I want to say I went all the way. It’s not far now. We can make it.”

Kathleen didn’t look very happy with my pronouncement. Perhaps she thought I was being a tad stubborn. Margaret suggested that maybe she could take some of our gear, to lighten our loads.

“No, thanks, it’s not too heavy.”

Kathleen had heard enough, and lifted her heaviest pack onto Margaret’s ski-doo.

We continued to walk, but still had not reached town by the time Margaret and Jo-Ellen had finished running the dogs. Margaret once again asked if we wanted a ride. Town was only about 300 m (yards) away, but the ski-doo trail went up and over the hill. I was pretty close – close enough to say that I had done it. The hill looked steep. It would be a lot of work pulling up the slope. I wasn’t that stubborn. We hitched our sled and toboggan to the ski-doos, and moments later, at 5:00 pm, after eight hours on the trail, we were shaking hands, for the first time, with Bern Will Brown himself.

By six o’clock we were enjoying the hospitality of Bern and Margaret’s dinner table. We felt very comfortable. It was good to get off the ice. It was good to rest out of the wind. After dessert and coffee, Bern handed us our mail, and showed us to one of his guest cabins. We lay down on the bed to read our letters. I had received a small package from Bill Owens, a friend that I have known since childhood. I slit open the box, and removed the packing material, which consisted of recent sports sections dealing with the upcoming baseball season. Owens knows that we love baseball. Within the packing material was another, even more prized and unexpected gift: a 375-ml flask of brandy. I had not been thinking of brandy, but brandy is exactly what I wanted at that moment. Letters were good; but letters with baseball news and brandy were truly excellent.

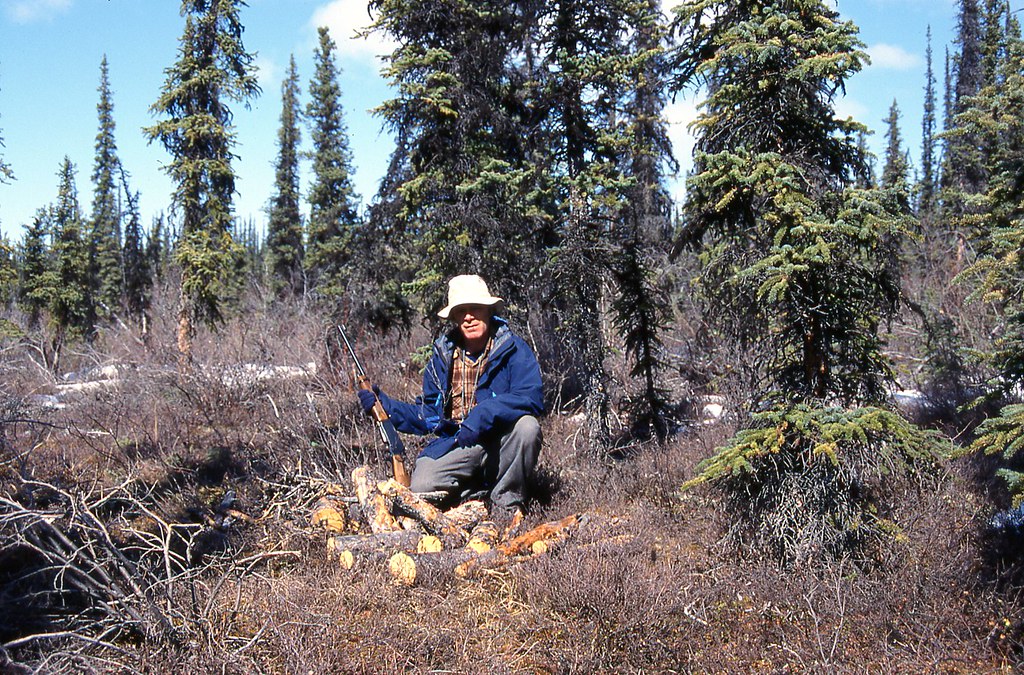

Bern Will Brown is a true icon of the North, and in the popular press his name is often considered synonymous with that of Colville Lake. Bern was born in Rochester N.Y. in 1920, and from a very young age became fascinated by the North. After becoming an Oblate of Mary Immaculate priest in 1948 he was sent to northern Canada. When Bern arrived in Colville Lake in 1962, only one other family remained in the traditional village. Most of the original inhabitants had moved to larger settlements, particularly Fort Good Hope. Bern envisioned a resurrected Colville Lake that would provide a refuge for native people to pursue traditional lifestyles of hunting and trapping, while also escaping the drawbacks of ‘modern’ city life such as alcohol and unemployment.

Indeed, after Bern built his log house in 1962, aboriginal people started to return. Bern eventually built a church called

Our Lady of the Snows, a nursing station, a museum and a library, which contains approximately 700 books on the North.

In 1971 Bern received permission from the Vatican to be married, and is now considered by the church to be a lay leader. Bern’s wife Margaret was born at Stanton, 18 km east of the mouth of the Anderson River on the Arctic Coast. Margaret raises a pure-white strain of sled dogs, and comes from a trapping family whose Texas father married an Inuit woman.

Much has been written about Bern, and rightfully so. He is extraordinarily accomplished and talented, along the lines of a Renaissance Man. As a priest with a classical background, he is obviously broadly educated and well read. He has written several books, is a gifted painter of northern landscapes, is fluent in the local language, is skilled with an axe and a chainsaw, and is completely at home out on the snow trail and living in the bush. I envy his talents.

Immediately after breakfast we headed off to the Co-op store to mail our letters. Then over to Robert and Jo-Ellen’s to call Kathleen’s mother on her birthday. Her parents had no idea that we would ever be coming to town. I’m sure that they sometimes felt they would never hear from us again. The call had to be very exciting. I’ll let Kathleen describe the call in her own words:

The phone rang, and my father answered. “Hello, Dad, it’s Kathleen.”

There followed just a little bit of silence, as he grappled with this unexpected information. “Kathleen! Where are you?’

“I’m in town. We came across the lake. Took us two days, but here we are. Is Mom there?

“She’s out at the store, she should be home soon. She will be so unhappy to miss this call. Tell me about your trip to town.” I gave him the main details, all the while wishing Mom would come home. Suddenly my father said, “I hear the door, your Mom is home.”

“Don’t tell her it’s me.”

I could hear their conversation on the other side. “Here, dear, there’s a call for you?”

“Who is it?”

“I don’t know. They just asked for you.”

“Hello?”

“Hi, Mom. Happy Birthday!”

Now there was a lot of stunned silence.

“Hi, Mom. It’s Kathleen. Happy Birthday!”

“Kathleen! Kathleen! Where are you?”

I told her of our trip across the lake to town, but left out all the scary parts about wind and blizzards and pressure ridges and hard work. No need to worry her. She was so excited and happy, and so was I, especially when she said, “You’re the first of my eight children to call me today.”

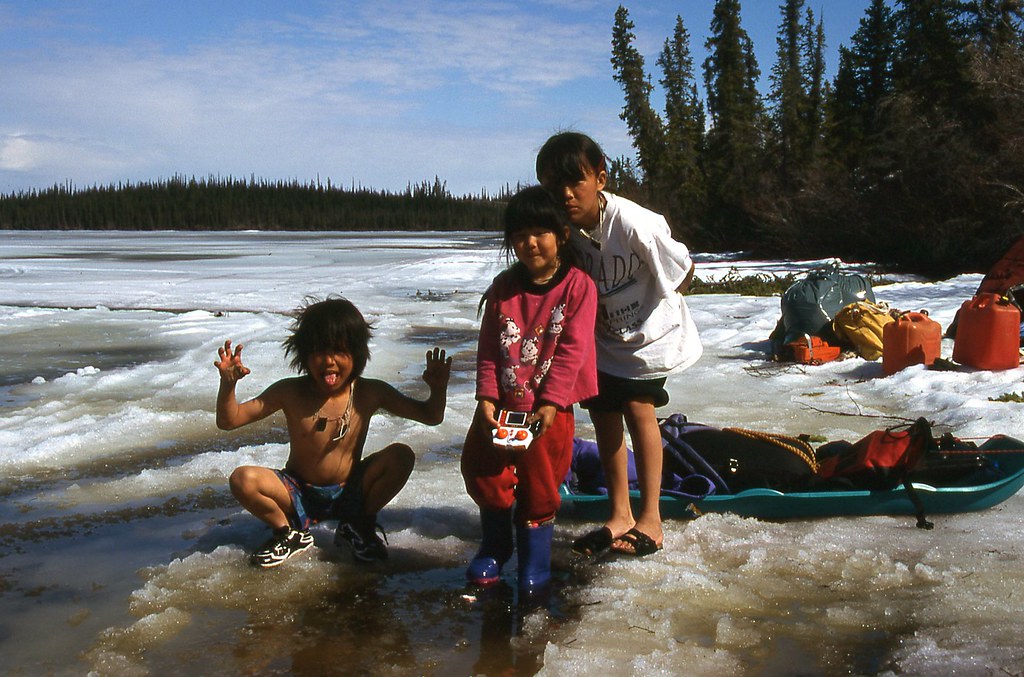

At the time of our visit, Colville Lake retained many of the qualities that Bern had hoped for. Most of the residents still pursued traditional activities such as hunting and trapping. The town itself was quite picturesque, consisting almost entirely of log houses. Electricity had arrived only very recently. No indoor plumbing existed, and residents were personally responsible for hauling their own drinking water in buckets from Colville Lake. A very rustic lifestyle, much like that which we were living at the North End.

In the afternoon we moved from Bern’s guest cottage to Robert and Jo-Ellen's house. I helped Robert replenish his household water supply. We hitched a sled to his ski-doo, and dragged a plastic tank 200 m out from shore to where a hole had been chiselled through about 75 cm of ice. I kneeled over the hole, and lifted buckets of water up and over to Robert, who poured it into the plastic tank. I must have lifted a hundred buckets, all with my left arm. The repetitive lifting ‘up and over’ part was not a good idea, as I think I might have damaged my left elbow, which is quite sore.

Our first day in town was the next to last day of the annual Spring Carnival. To us, people from the South, many of the competitive events were entirely new, including ice chiselling, snowshoe biathlon, tea boiling, bannock making, ski-doo races, dog team races,

andcaribou head skinning. There was approximately $40,000 in prize money available, which seemed pretty substantial for such a small town. Bern said that the Federal Government, with some corporate donations, was the primary source of the prize money, which was intended to support traditional customs and games. I think that an additional underlying goal was to provide cash to people living in small, northern communities, most of which suffer high unemployment rates.

For example, most of the Colville Lake events were divided into age classes, and some were restricted to either male or female entrants. The top three finishers in each category won cash prizes, and very few categories had more than three entrants. Pretty much everyone who participated in any event finished in the money.

One elderly lady had entered the snowshoe biathlon, which required the participants to snowshoe around a fairly lengthy course on the lake, and to shoot at balloons hanging at various stations. She was an expert markswoman, and never missed a shot. It was painful, though, to watch her hobbling around the course, coughing and wheezing all the way. At the end of the race, in which she finished a very distant third, Jo-Ellen asker her if she felt OK.

“No, I have a bad cold.”

“Why did you enter, then?”

“Because I need the money.”

I admired her determination and integrity. Despite her age, and despite her poor health, she asked for no special concessions. She competed according the to the rules. She struggled to the first station, raised her gun, and hit all the balloons. She sheathed the rifle on her frail back and continued to each of the successive stations with equal success. She finished the race, and earned her prize money.

Spring Carnival in Colville Lake stretched over four days for several reasons, including snow conditions, and the need to share dog teams and equipment. Events rarely started on time. Most importantly, though, Spring Carnival in Colville Lake was truly a celebration – a time to share memories – a time to socialize. Because we were totally unexpected strangers in town, people were naturally curious about what Kathleen and I were up to. They were surprised, and a little concerned that we had crossed the lake, during what they said was the worst storm of the winter. “We’re glad you made it. The houses here in town were shaking in the wind. We didn’t know that you were coming to town across the lake. If something had happened to you on our land, we would have felt responsible.”

A native man, Gene, volunteered to take us back to our cabin by ski-doo. We accepted his offer. I have already dragged to town, and am pleased to know that I can do it. At this point, neither Kathleen nor I really want to struggle back to the cabin, although I would enjoy camping on the ice, in good weather. Even so, I asked Gene when it would be convenient for him to take us back, and he suggested early on Wednesday morning, four days from now. That’s a little bit longer than we had planned to stay, but we were glad for the ride.

The afternoon was clear, calm and warm at +11 C (52 F). The first Snow Bunting of the year arrived, which is the surest sign that spring is coming. We again appreciated the hospitality of Bern and Margaret, who hosted us for dinner, along with Robert, Jo-Ellen and Carroll McIntyre, the manager of the Co-op Food Store.

The day had been sunny, calm and warm, with lots of snow melt. The sun didn’t set until about 10:00 pm, and it was light until well beyond 11 o’clock. Before going to the Spring Carnival dance, Kathleen and I stood quietly out at the edge of the lake to watch the glorious deep-crimson, everlasting sunset that filled the entire horizon. We read in the Norman Wells newspaper that on April 31st there will be 19 hours and 33 minutes of daylight in ‘The Wells.’ Our home at the North End of Colville Lake is more than one degree of latitude farther north than Norman Wells, which means that we should have close to 20 hours of visible light by the time we return to our cabin. Only three weeks after the vernal equinox, and already darkness is becoming a meaningless concept. We are free to travel, work, play and sleep whenever we want. At the North End of Colville Lake, we will be gaining close to one hour more of light per week. Light is good. More light is better. All light is best. I look forward to the constant daylight of mid-summer.

Next Wednesday began calmly enough. We woke late, lingered over our breakfast, and wandered over to Bern’s compound to retrieve our sled, tent, snowshoes, lawn chair and other camping gear that we had stored in his warehouse. We dragged it all back to Robert and Jo-Ellen’s, and left it by the side of the road. We climbed up the stairs back into the house, boiled up some tea water, and began packing our clothes and bedding. Little by little, in between sips of tea, we had finally gathered all our possessions in one spot. At 11:30 we sat outside eating sandwiches. We were ready.

Noon came with no sign of Gene. We weren’t worried, though. Things always happen according to their own time. About 12:30, someone sauntered by to say, “Gene says he might not be going today. Maybe tomorrow. He’s not sure.”

Oh well, he’s probably just busy doing something right now. The days are long. Kathleen and I were both confident that we would actually be going today. We continued to sit outside, drinking tea, and enjoying the sunshine.

People began to cluster around, and were naturally interested in the kind of equipment that we had brought. A man picked up one of the snowshoes, and balanced it thoughtfully on his right hand. He turned it over, quietly assessing its shape. I knew that he must be thinking that our snowshoes were pretty heavy, that they tilted forward, and that they might not be the best shape for travel through deep, soft snow. He set the snowshoe back on the pile, looked up, and simply asked “How you chase moose through bush on these?” He didn’t want to say that my snowshoes were poorly matched for local conditions. That would be undiplomatic. And it has been my experience that native people prefer diplomacy to confrontation. They tend to prefer rhetoric to direct criticism.

Another man picked up our ice chisel and asked, “What’s this for?”

“I brought that just in case we couldn’t find enough snow to melt when we were camping on the lake. I thought I might need to chisel through the ice to get water.”

“Pretty heavy to carry all that way.”

A simple comment that neatly summarized his true opinion, which was probably something like “there’s always plenty of snow out on the lake, and besides, do you know how long it would take you to chisel through ice that’s usually more than a metre (three feet) thick? You’d die of thirst or exhaustion before you could chisel through with this.” He didn’t say it was a bad idea. He didn’t say that bringing it just meant that I had to work harder. He didn’t say that it’s not a good idea to be dragging things I don’t need. That would be undiplomatic, so he just said it was pretty heavy to carry all that way.

Just before four o’clock, Gene came down the hill, dragging a toboggan behind his ski-doo. “I’ve just gotta finish doing a few things at home. Load your stuff in the toboggan. I’ll be ready to go at 4:30. It should be fun.”

This news created a great deal of interest in our journey back to North End. School would be out for the day by the time we would leave. Robert and Jo-Ellen said they would like to come with us. Doug, an administrator with the Board of Education, was in town to review the school curriculum. He’d never been to Colville Lake before. He’d hardly ever been on a ski-doo before. It sounded like a grand adventure to him. He would like to come too. An RCMP officer, Jean-Marc, was in town on his monthly visit from Fort Good Hope. He’d never been north of town before. “I’d love to come,” he said.

And of course Margaret wanted to come. She’s always ready for a ski-doo trip. “You can ride with me, Kathleen,” she said. “I’ll get some food together. We can have dinner out at the cabin. Just come by the lodge when you’re ready.”

It was a beautiful evening, and everyone wanted to go to North End.

At 4:30 we were mostly packed, so Kathleen started walking to the lodge to meet Margaret, who showed up a few minutes later on her ski-doo looking for Kathleen. “You just missed her, Margaret. She’s probably waiting for you right now over at your place.”

Margaret roared off and Gene arrived a few minutes later. Without saying a word, and without turning off his machine, he hurriedly threw the rest of our gear into his toboggan. Gene seemed to be in a rush for some reason. Without warning, he turned the throttle full open and sped away, without even folding and tying the toboggan wrap. Like catching a train leaving the station, I ran after Gene’s accelerating ski-doo and just managed to jump on back of the toboggan.

Gene and I raced through town. The treads of the ski-doo kicked out mountains of snow, which filled the open toboggan and covered our gear in wet slush. As we sped onto the lake, we spotted Margaret up ahead, all alone on her ski-doo. Where was Kathleen? She’s supposed to be riding with Margaret. Where was everybody else? They must all still be back at the loading site, waiting for us.

We roared back through town, up and down all the streets, without finding any of our entourage. We thundered back out through town and onto the lake, where a cluster of three ski-doos waited for us. Kathleen was riding with Jean-Marc, Doug with Margaret, and Jo-Ellen with Robert. We were all together and ready to go. Gene turned off the motor, and still without a word, threw all our stuff onto the ice, emptied the deep slush from his toboggan wrap, reloaded everything, and then wrapped and tied the tarp securely over the load. A little bit like closing the barn door after the proverbial horse has run away. It would take days for our soaking gear to dry out.

We now headed north, with Gene in the lead. The other three ski-doos quickly fell behind and dropped out of sight. Gene was definitely in a hurry. After about 10 km (6 miles) Gene decided to stop and wait for the others. I think he really had no choice, as his skidoo was over-heating. Still without saying a word, he turned off the engine and lifted up the hood. The others arrived a few minutes later, and they likewise lifted the hoods on their ski-doos to cool them off. The evening was warm, and the snow was thick and slushy. The ski-doo engines were working hard, and being pushed to the limit.

A few minutes later, we blasted off again, even faster than before. We were going hell-bent for leather. I have no idea why that phrase means going fast. But I like the way it sounds. You just know that you’re going fast when you’re going hell-bent for leather. Gene and I sped past the Tent Camp on the Big Island. I looked back and could see only Jean-Marc and Kathleen, fairly close behind, and gaining. Jean-Marc eventually pulled up beside us, which seemed to surprise Gene, who I’m sure thought he could never be caught. And certainly he didn’t like being caught. Jean-Marc presented too much of a challenge, and this could not be tolerated.

After the Big Island, the ski-doo route crossed two more islands where the ‘portage trail’ wound around and through the trees. The race now demanded not only speed, but also required skillful maneuvering. And Gene was very skillful. We raced over the portages, barely slowing down, with Gene hanging off to one side or the other of his ski-doo as we rounded the turns. I was now being drenched in snow and slush, and could barely hang on as the toboggan swerved and careened through the trees. But I was determined not to fall off. I was determined not to be just one more crazy city guy from the South who couldn’t handle a little ski-doo ride.

Finally, at 6:45, we reached the cabin, and came to a merciful stop. Without a word, Gene tossed all my gear out, sat down on his ski-doo, and began to eat a lard sandwich. A man needs a lot calories when working so hard out in the bush. There was no sight or sound of any other ski-doos. I asked Gene if he wanted to come in. We could start a fire, and boil up some tea water. “No.” Something seemed to be bothering Gene, but I had no idea what it was.

After about 10 minutes Gnee rumbled back down to the lake at 6:55. Still no sight or sound of our travelling companions.

I went into the cabin, started the fire, and began to unpack our gear. At 7:30 I heard the sound of an approaching ski-doo. It was Gene, with Kathleen on the back, and Jean-Marc riding in the toboggan. Just after Gene and I had pulled away from them on the Big Island, their ski-doo had begun to backfire, and finally broke down on the last portage trail. Jean-Marc had replaced the spark plugs, but still couldn’t get his ski-doo to start. Gene dropped off Kathleen and Jean-Marc, and then left again ‘to go caribou hunting.’

At 7:50 Robert and Jo-Ellen arrived with news that Margaret and Doug had broken down near the Tent Camp on the Big Island. Robert and Jo-Ellen had brought a full 100-pound propane cylinder, which Bern said we might need before the winter was over. Jean-Marc, Robert and I wrestled it into place on the porch. Kathleen invited everyone inside for tea, but our guests said they couldn’t stay. “We have to get going to find Margaret and Doug.”

We stood around outside chatting, and commenting how warm the weather had become. How the weather had become too hot for driving ski-doos at top speed. At 8:30 Jean-Marc, Robert and Jo-Ellen left to find Margaret and Doug. Kathleen and I were alone again at our cabin. We were disappointed that our guests couldn’t stay for dinner, or even tea. Kathleen had also brought some coffee back, as a gift from Margaret for the party planned for tonight. There would be no dinner party now, though. What had started out as a calm morning ended up as a very rushed, chaotic and disappointing evening.

During our absence, a great deal of melt had occurred. The south-facing knoll near the flagpole now showed bare ground. The pier extended over open water. Our cabin roof was snow free. Our front yard was a morass of mud and wood chips. Open water extended along the shore south of the cabin. I felt restless, uneasy, and depressed. The winter I had come north to enjoy seemed over, yet canoeing season was likely still two months away

We spent the next day indoors, reacquainting ourselves with the comfortable routine of life in our cabin. A slow breakfast toasting bread and warming tea on the wood stove. Snacking on popcorn with our evening game of cribbage. Kathleen scored a 29-point hand tonight, the first time I have ever seen this maximum score in my entire life. And I’ve played a lot of cribbage since I was about eight years old.

The temperature remained between - 8 and -4 C (17 and 25 F) all day. Mild, but wet. I wish for either colder or warmer temperatures. This shoulder season is so uninteresting. This afternoon we saw a group of approximately 45 caribou standing and sitting on the ice 200 m (yards) from the cabin. They looked serenely ghostly as the misty snow swirled about them. After a few hours they drifted away to the northeast, toward Ketaniatue Lake. We had enjoyed going to town last week. At times we also enjoyed being in town. It’s good to be home, though.

Before we left for town Kathleen had been feeding a Whiskey Jack that had become quite attached to her. The bird would follow her whenever she strolled down Privy Path, and would perch next to her as she settled in at the end of the trail. Kathleen said that the bird just seemed to like ‘talking’ to her. This morning he (or she) spotted Kathleen as she walked down the path, and swooped along beside her, chattering away. When Kathleen stopped to say hello, he (or she) flew right down to the branch by her face and, as Kathleen says, “went on and on, changing sounds and puffing himself up. He sure had a long story to tell! He must have missed me.”

That’s how Kathleen tells the story. I didn’t actually see this myself, so can not verify its accuracy. I believe it happened though, just that way. Kathleen wouldn’t make it up, and the Whiskey Jacks certainly do know us by now. It’s good to be home, among friends.

On April 25, after a breakfast of bannock, we snowshoed up Woodlot Way and then turned southeast down Winter Camp Walk toward our campsite of last March. We hadn’t travelled this way since Kathleen’s birthday dinner more than two weeks ago. At that time, only we were using the trails. Since then, however, many caribou have passed along, across and over our carefully-made paths, which are no longer smooth, continuous and pristine. All seems in upheaval.

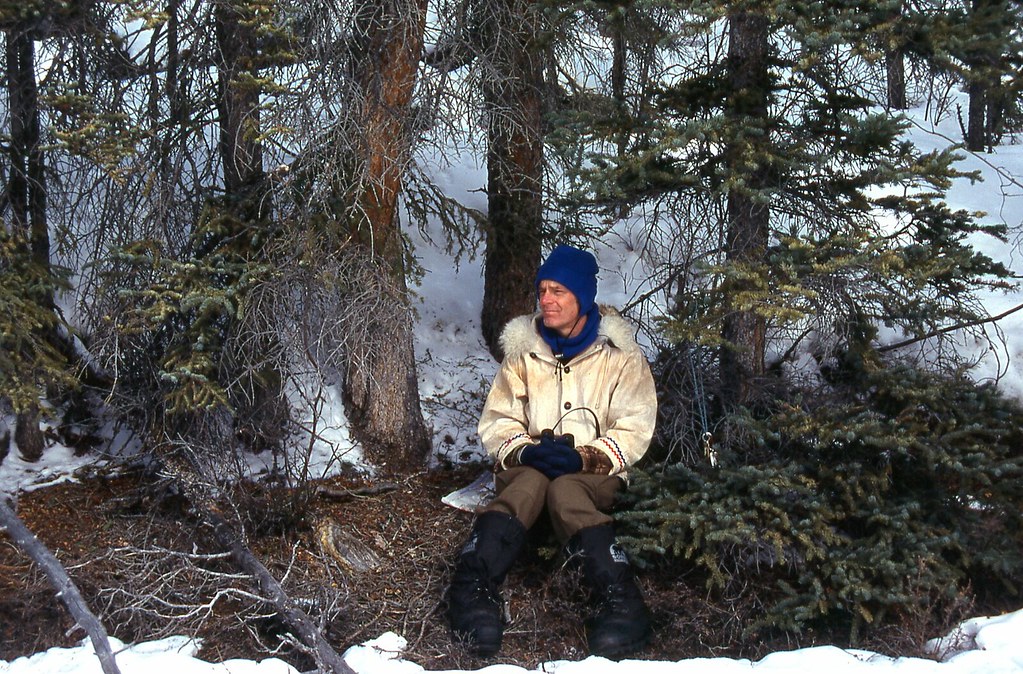

We reached the little narrow valley that we call Winter Camp II. Again we delighted in its idyllic beauty. For lunch we stopped on the south-facing bank of the stream, where we sat on dry, bare ground; a small rectangular patch, about 1 x 2 m (3 x 6 feet), but dry ground nonetheless! The sweet scent of crushed White Spruce boughs made me long for summer, which certainly looms nearer. All along the river, open patches of ground punctuated the south-facing hillsides. Throughout the valley, the snow was now crusted, and often not more than 0.3 m (1 foot) deep.

Just as we neared the mouth of the river, near Colville Lake, we found a 1-m-long (three feet_, 25-cm-diameter (10 inches) log of sawn white spruce. Someone must have dropped it here last fall. A great find! I loaded it into the toboggan, and cut, split and stacked it as soon as we returned to the cabin. The ‘new’ wood should provide two additional evenings of warmth, between cribbage and bedtime. One can never have too much wood.

There was no wind today, and we felt very warm and comfortable outside at -4 degrees. Kathleen is now wearing her light silk long johns, and talks about putting her heavy wool underwear away for the winter.

On April 26, in the late afternoon, before dinner, we returned to the open river. We showshoed through a land seemingly divided against itself – a land seemingly uncertain of its future. The continuous north wind of the last six days, with its accompanying cold temperatures had refrozen some previously open sections.

Yet the ground surrounding the trees, particularly larger trees on the west-facing bank, continues to expand, revealing Northern Labrador Tea, blueberries and Kinnikinnick. Common Juniper lies exposed on south-facing knolls. Even the east-facing ridge of the Ross River, the side of the ridge that has not yet enjoyed the light of the afternoon sun, is pockmarked with bowl-shaped cavities. For two weeks now we have seen a Bald Eagle soaring overhead. Snow Buntings flew past the cabin this morning. If only a southeast wind would appear for a week, then spring would surely rush forth to re-claim the land.

Just before dinner, at about 7:30 pm, a ski-doo raced into camp carrying Gene’s son George, and his wife Snowbird. Very exciting to have visitors! George said that we should have warm weather in another week, with only one more cold snap, of 2 to 3 days, in May. “Ducks should arrive in two weeks. One of the first places they come is here, because the outlet of the lake is the first open water. You’ll have a lot more visitors then, as people will be out hunting. They want to get fresh meat.”

He also said that, “the ice will start coming away from the shore of Colville Lake in early June.” That would be great. That means we might be able to paddle to town in only another six weeks or so.

We thanked George and Snowbird for their visit, and welcomed them to drop by again, anytime they were in the area. We also gave them a bag of brown sugar and three kg of shortening for Gene, as gratitude for bringing us back to the cabin last week.

On April 30, the weather is definitely warming. Plus 2 C (36 F) at 5:00 pm, and still zero (32 F) at 9:30. The day brought many indicators of spring. Large, wet flakes of snow falling heavily to earth. Snow Buntings flying north past the cabin. A Bald Eagle soaring above the river. Caribou migrating to the northeast. The aroma of moist earth permeating the air. More water opening up beneath the pier. Oh, it's happening now! Spring rushes north as winter retreats.

Just after 10:00 pm. Tommy and another younger man staying at the Tent Camp on the Big Island stopped by to borrow some salt. Tommy reports that ducks have arrived in Fort Good Hope. He expects no more cold snaps, and I believe him.

On May 1, I bucked up most of the two trees I felled last week, and again re-stacked the wood on the porch. I believe that we have enough wood to take us through to the end of our stay here, but will make a more definitive assessment tomorrow, when I’ve brought all the wood back to camp. While snowshoeing back from the wood lot, I actually ‘felt’ like spring, which is no longer just a prediction or a concept or a hope or my fantasy. The day was warm and sunny.

The open water under the pier expanded even overnight, and opened up considerably more during the day. I stood on the pier in the evening, gazing at the water, which appeared so fresh and new and enticing. Snow Buntings passed overhead on their journey north. Whiskey Jacks foraged at the edge of the retreating snow pack, snapping up food morsels that had remained hidden since the first permanent snow of last October.

Shortly before 10:00 pm we heard a motor approaching from the south. Moments later we spotted a lone ski-doo, driving hard directly toward the open water at the outlet of Colville Lake. What was he doing? No one ever comes directly to the outlet. Even Ron, way back in February, headed to the shore before reaching the outlet. Everyone knows that the ice remains thin and dangerous at the outlet, even in mid-winter. Everyone knows that the outlet is open by May!

We ran down to the pier, waving our arms, and gesturing to the rider to head to his right. The ski-doo continued onward, unwavering, toward the outlet. We started shouting, jumping up and down, and waving even more wildly. Still the rider continued straight ahead. We finally caught his attention, less than 50 m (yards) from the open water, when he quickly veered right and charged his ski-doo up the bank below the cabin.

It was a young man, someone we had not seen in town. He had been drinking, and was quite unsteady. “Would you like to come inside, and have some tea?”

“Yep.”

We sat down at the table, where our visitor, I’ll call him ‘Young Man,’ became quite talkative. YM was about 25 years old, tall, muscular, and in the prime of his physical life. Although his English was rudimentary, we gleaned that he had been drinking with friends at the camp on the Big Island, when the discussion had turned to ski-dooing prowess. YM apparently claimed that he knew everything about travelling through the bush on ski-doo. Boasted that he could ski-doo down the Ross River, beyond where the river knifed through Colville Ridge. He could then skirt west behind the ridge, cross back over the ridge by a route that only he knew, and be back to the Tent Camp, after 25 km, in a time so short as to be unbelievable. Or something like that.

Needless to say, his friends expressed skepticism, even outright doubt. So here he was, drinking tea at our table, and determined to go on.

“I think your friends are right,” I said, “We walk along the river almost every day. There’s a lot of open water. The banks are steep in many places. It would be difficult for a ski-doo. I don’t know where you want to cross, but pretty much the entire lower third of the river is completely open.”

“You got map? I can show.”

I spread the map out on the table. YM bent over, tracing his finger along the contours. We stood behind him, bent over his shoulder, eager to see where this secret trail might exist. We love trails. YM turned his head toward us and said, “I’m afraid.”

“Why?” I thought that maybe he had forgotten where the route was, or that he had realized that his adventure might actually be dangerous.

Instead, YM simply said, “Never been all alone with white people before.”

That answer surprised us. We had actually been feeling a little afraid ourselves. Kathleen and I are both physically small and no longer young. We were now all alone with a young, strong man who was drunk. A man whom we did not know. A man who might be unpredictable. And he was afraid of us. It seems that all three of us had become victims of stereotypes. All three of us were afraid of our suddenly unfamiliar circumstances.

“No need to be afraid of us. Would you like some more tea?”

YM continued to look at the map, and then asked, “Why you here?”

We told him that we had come at the end of January to enjoy the winter, and then to paddle down the Ross River to the Anderson River, and eventually to the Arctic Coast. Now he became very interested in our map, and began to point to places along the river between our cabin and Ketaniatue Lake. “Shallow here. Rapids here. This part easy.” He was eager to help – eager to help visitors in his neighbourhood.

YM then stood up and pulled out a knife that had a blade approximately 25 cm (10 inches) long. It was a big knife, used for skinning caribou and moose.

What the hell was happening now? He held the knife out toward us, and said, “Here. Gift. My grandmother make handle. I give to you.”

This took me aback. It also worried me, perhaps more than if he had meant to stab us with the knife. He was drunk, and still very unsteady. So maybe we could have taken the knife away. Instead of physical confrontation though, I faced an awkward social situation. Should I take the knife that his grandmother made? If so, how would YM feel tomorrow morning, when perhaps he would want his knife back? What if I didn’t take the knife? Would YM feel insulted? Worse yet, would YM become angry?

“Thanks very much. But I can’t take your grandmother’s knife. She made it for you, not for me. You need to keep the knife. To remember her by.”

YM sheathed the knife, and sat back down. Maybe he was happy with my answer. He had made the offer. He had done the right thing by offering a gift to his visitor. I only speculate though, as YM said nothing.

Just before 11:00 o’clock, three ski-doos arrived. The men had come to retrieve YM. They couldn’t stay for tea, but Tommy said he would stop by tomorrow.

May 4 began dull and grey. We spent much of the day indoors. We sat quietly at the table reading and writing. In the afternoon we snowshoed out to the Wood Lot to retrieve the last of the kindling from the felled trees. Ski-doos had travelled up Woodlot Way. They had even turned west to rumble along our own, private Riverside Drive. We no longer live alone in an isolated, boreal forest.

The ground continues to expand everywhere and multitudes of trees and shrubby twigs have ‘sprung up’ in the middle of our snow trails. On the south-facing knoll below the flagpole, Prickly Saxifrage has sprouted new leaves beneath its bright red leaves of last year. The snow next to the shore below our cabin is melting. Soon, perhaps, open leads will develop, through which we can paddle our canoe. For the past few days a muskrat has taken up residence at the base of the hill below our cabin, and it often sits on a ledge of ice, sunning itself next to the open water.

May 7 was a clear morning made to feel cold by the strong, persistent southeast wind. We dallied and lingered in the cabin, waiting for warmer, calmer conditions before heading out to the Tent Camp. After lunch we acknowledged that we had sunk to a pathetic state. We had become downright fainthearted. Two months ago we happily went out at -30C (-22 F) even with a strong wind. Now we seek shelter from the wind at only -5 C (+ 23 F). We have become soft and timid. How quickly our perspective has changed to accommodate current conditions.

After a suitable self tongue-lashing, we set out for the Tent Camp at 12:45. Just before the first island portage, about 200 m (yards) up the trail, we saw a lone figure jumping up and down wildly, like a man swatting at a swarm of stinging bees. Everyone we had met since arriving at North End was invariably calm, no matter what the situation. No one ever became excitable or demonstrative. My first reaction was “what’s a white guy doing way out here?” This thought struck me as somewhat ironic, as I myself was a white guy, and I was way out here. Irony aside, the agitated person up ahead was certainly not from around here.

As we approached, the man started coming up the trail toward us, carrying a briefcase, which confirmed my first impression. Has to be a white guy. By then the stranger saw us, and waited for us to join him, where he stood beside his four-wheeler, which had become stuck in the deep snow next to the ski-doo trail.

“Hi,” I said. “My name’s Mike. This is my wife Kathleen.”

The man held out his hand and said, “I know. My name’s Jamie. I’m the resource conservation officer in Norman Wells, and was in town, so thought I would come out and visit you. My machine is stuck, though. I was going to walk the rest of the way. It’s not very far is it?”

“No, not too far. So how come you’re riding a four-wheeler?”

“Ski-doos break down a lot in warm weather. I’m more used to four-wheelers anyway, and it worked fine when I was on the ice on Colville Lake. I didn’t expect so much snow though, after the Big Island.”

“So did you happen to bring any mail for us? We were going to the Tent Camp to get mail that Margaret Brown said would be there for us.”

“No, I was just coming straight to your cabin. I didn’t stop at the camp. I do have a

Mackenzie Valley View newspaper and an

Up Here magazine for you, though.”

“Thanks very much. It’s always nice to get reading material. It’s still about 2 km to our cabin, and the snow is deep in spots. Why don’t we just help you get unstuck, and we can all go back to the Tent Camp?”

So with all three of us straining, we pushed the four-wheeler back up onto the hard-packed ski-doo trail and continued to the camp, where we enjoyed three hours of chatting and drinking coffee and tea in Tommy’s wall tent. James and Sharon had moved their camp 1 km across the bay to where they are building a cabin on the mainland. They had left four pieces of mail for us, a primary reason for today’s 12-km (7.5 miles) round trip.

The travelling conditions on the way out to the Tent Camp, even without snowshoes, were fairly good. The snow crust was firm, and we broke through only a few times. On our return to the cabin, however, the snow had softened in the plus two-degree (+36 F) heat, and we repeatedly broke through. Even so, we persevered without putting on our snowshoes. We’re tired of using them, particularly as the lamp wick bindings seem to work themselves loose quickly in the warmer weather. And indeed, the days are definitely warmer. Even at 10:00 pm the temperature was still zero degrees (32 F).

Kathleen’s feelings about the last two days are summarized below:

Yesterday it was obvious that everything had changed. Although the overnight temperature still fell below zero (32 F), and although we still gazed out at a frozen, white expanse on Colville Lake, I felt that winter was over. As we walked to the Tent Camp, the air felt warm despite the strong wind. People have been out and about for the last couple of weeks and yesterday we met Jamie, who told us that the ice moved 200 metres (yards) on the Mackenzie River at Fort Simpson a day or two ago. Norman Wells should see movement in a week. The ice bridges on the Peel and Mackenzie Rivers on the Dempster Highway are closed. It is happening and you can feel everyone’s excitement. The snow is soft and wet. The sound of dripping is everywhere, and puddles sit in the hollows. The sun is setting close to midnight and daylight now extends for 24 hours. The thaw we see today will only escalate. Yes. Everything has changed.

On May 8, I was I’m willing to say that spring arrived. The temperature remained warm overnight, falling only to -2 C (+28 F). The cabin interior this morning was +8 C (+46 F) even before lighting the fire. The most excitement though, occurred when we went outside this morning and saw eight Herring Gulls sitting on the ledge of ice. We listened all morning to the sound of their calls during flight, which undeniably announces to us that spring has arrived. How many more bird species must be on their way right now?

In the afternoon Tommy rode up on his ski-doo and asked, “Have you seen any geese or swans?”

“No, we haven’t, but we have seen Herring Gulls.”

“Well, I saw some geese fly over the Tent Camp this morning. You should see them soon.”

Tommy wasn’t interested in Herring Gulls. He was carrying a shotgun, and drove off looking for fresh, succulent meat. About 30 minutes later four Canada Geese arrived, and as we stood in the warm afternoon sun with our binoculars, we saw a shore bird on the edge of the ice. Too far away to know what species of shore bird, but it was probably a Greater Yellowlegs. A large pan of ice, the largest pan of ice so far, maybe 7 m (yards) in diameter, broke free from the shore and floated off down the Ross River. We reached our highest temperature of the winter, +6 C (+43 F) at 4:00 pm. A solitary housefly buzzed happily on the west-facing side of the cabin, soaking up the sun’s warmth.

By mid-evening, 20 Herring Gulls sat on the edge of the ice, hunkered down, facing into the southeast wind. Behind the cabin, in the lower branches of a white spruce tree, a small spider dangled in the air, spinning its web. We also saw a Northern Hawk Owl hovering near the top of the pole supporting the radio antennae wire. Although the Northern Hawk Owl is a resident species, we had not yet seen it this winter. It is as though the owl simply wanted to join the crescendo of life reappearing before our eyes.

------------------------------------------------------

It's that time again. Dog's gotta walk.

-----------------------------------------------------