- Joined

- Aug 21, 2018

- Messages

- 1,805

- Reaction score

- 4,496

Thanks for your encouragement, Alan & Ralph!

The Barren Grounds are like a northern prairie, and we thoroughly enjoy the juxtaposition of sky and water, particularly when suffused with light on the ever-present horizon.

Splashes of colour along the shore often draws our attention. This river beauty (Epilobium latifolium) is a close relative of fireweed (Epilobium angustifolium) and one the first species to establish along disturbed river banks.

Other plants sheltered among the rocks of the river bank include prickly saxifrage (Saxifraga tricuspidata), a cushion plant. The dead leaves form a "mounded cushion" that shelters the plant from snow abrasion in winter and from drying out in summer.

Mountain avens (Dryas integrifolia), the floral emblem of the NWT is also a cushion plant, which is a common plant adaptation to wind in the north. Although wind often presents a problem, many plants also take advantage of the wind, which helps distribute the plumed seed of mountain avens far across the northern landscape.

Antler lichen (Masonhalea richardsonii) also takes advantage of the wind. It grows unattached to any substrate, and rolls along the ground, eventually accumulating in its preferred moist, tundra depressions. (Thelon River)

All living things in the north need to be well adapted to survive, particularly to economize heat. The Lesser Fritillary settles on spike-like goldenrod (Solidago spathulata) and spreads its wings in a way that maximizes the warmth it can absorb from the sun. (Snowdrift River)

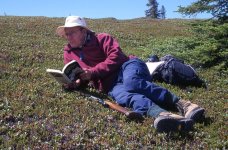

Warmth is important even to canoeists. Kathleen relaxed at lunch, enjoying the heat that is captured by the weathered rock. (Point Lake, Coppermine River)

The tundra lakes, when they are calm, are truly spectacular and comfortable. We glide effortlessly down Point Lake, along the Coppermine River. We stop in a serene bay named for Keskarrah, one of the guides for Sir John Franklin on his ill-fated overland expedition to the Arctic coast in 1821.

I loved looking at and being near these rocks. We our now on the Canadian Shield, whose rocks form the nucleus of the North American continent. The Himalayas are 35 million years old; the Rockies are 60 million years old; but this eroded core of former mountains was created between 2.5 and 4 billion years ago. They are among the oldest rocks on earth. (This was true in 1995. Our knowledge and understanding might have changed since then.)

These rocks support an interesting array of lichen species. Map lichen (Rhizocarpon geographicum) and rock tripe (Umbilicaria spp.). The rock tripe was made infamous by Sir John Franklin's 1821 expedition. Returning to Fort Enterprise from the Arctic coast in late fall, much of what they survived on was this lichen.

Many lichens require specific kinds of habitats. Blood spot lichen (Haematoma lapponicum) grows only on acidic, usually granitic rocks (rock tripe lichen grows nearly exclusively on acidic rocks).

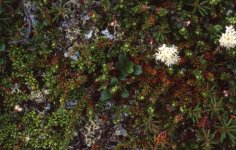

Other lichens such as few-finger lichen (Dactylina arctica), grow best on soil, on moist sites protected by snow banks that persist late in the year. (Thelon River)

Worm lichen (Thamnolium subuliformis) also thrives in these snow patch communities, and together with few-finger lichen, is commonly used for nests by ptarmigans, plovers, and sandpipers. (Thelon River)

Least willow (Salix herbacea) occurs in moist areas where the snow persists until late in the season. It must flower and produce seed very quickly, because it has sunlight for such a short period after the snow melts. (Snowdrift River)

The Barren Grounds are like a northern prairie, and we thoroughly enjoy the juxtaposition of sky and water, particularly when suffused with light on the ever-present horizon.

Splashes of colour along the shore often draws our attention. This river beauty (Epilobium latifolium) is a close relative of fireweed (Epilobium angustifolium) and one the first species to establish along disturbed river banks.

Other plants sheltered among the rocks of the river bank include prickly saxifrage (Saxifraga tricuspidata), a cushion plant. The dead leaves form a "mounded cushion" that shelters the plant from snow abrasion in winter and from drying out in summer.

Mountain avens (Dryas integrifolia), the floral emblem of the NWT is also a cushion plant, which is a common plant adaptation to wind in the north. Although wind often presents a problem, many plants also take advantage of the wind, which helps distribute the plumed seed of mountain avens far across the northern landscape.

Antler lichen (Masonhalea richardsonii) also takes advantage of the wind. It grows unattached to any substrate, and rolls along the ground, eventually accumulating in its preferred moist, tundra depressions. (Thelon River)

All living things in the north need to be well adapted to survive, particularly to economize heat. The Lesser Fritillary settles on spike-like goldenrod (Solidago spathulata) and spreads its wings in a way that maximizes the warmth it can absorb from the sun. (Snowdrift River)

Warmth is important even to canoeists. Kathleen relaxed at lunch, enjoying the heat that is captured by the weathered rock. (Point Lake, Coppermine River)

The tundra lakes, when they are calm, are truly spectacular and comfortable. We glide effortlessly down Point Lake, along the Coppermine River. We stop in a serene bay named for Keskarrah, one of the guides for Sir John Franklin on his ill-fated overland expedition to the Arctic coast in 1821.

I loved looking at and being near these rocks. We our now on the Canadian Shield, whose rocks form the nucleus of the North American continent. The Himalayas are 35 million years old; the Rockies are 60 million years old; but this eroded core of former mountains was created between 2.5 and 4 billion years ago. They are among the oldest rocks on earth. (This was true in 1995. Our knowledge and understanding might have changed since then.)

These rocks support an interesting array of lichen species. Map lichen (Rhizocarpon geographicum) and rock tripe (Umbilicaria spp.). The rock tripe was made infamous by Sir John Franklin's 1821 expedition. Returning to Fort Enterprise from the Arctic coast in late fall, much of what they survived on was this lichen.

Many lichens require specific kinds of habitats. Blood spot lichen (Haematoma lapponicum) grows only on acidic, usually granitic rocks (rock tripe lichen grows nearly exclusively on acidic rocks).

Other lichens such as few-finger lichen (Dactylina arctica), grow best on soil, on moist sites protected by snow banks that persist late in the year. (Thelon River)

Worm lichen (Thamnolium subuliformis) also thrives in these snow patch communities, and together with few-finger lichen, is commonly used for nests by ptarmigans, plovers, and sandpipers. (Thelon River)

Least willow (Salix herbacea) occurs in moist areas where the snow persists until late in the season. It must flower and produce seed very quickly, because it has sunlight for such a short period after the snow melts. (Snowdrift River)

Last edited: