The next day was clear, but cool (4 degrees C. 39 degrees F) and windy, as we stopped for lunch near the northern limit of trees in the September Mountains.

Lunch in the September Mountains, a little upriver from Melville Creek.

Kathleen and I regularly gave slide shows at hospitals and long term care facilities when we lived in Vancouver. We began our Coppermine show with the following quote.

It is said that a long time ago an Inuk, who was named Upaum, was being chased by a brown bear. As he ran north he bent down and drew a line with his finger in the earth. Immediately a great stream of water gushed along the line, and grew into a huge river, saving Upaum. This great river flowing north became the Coppermine.

At one presentation at a long term facility, when we finished the quote, a lady from near the back said

If you are not going to tell the truth, then we are not going to listen.

Apparently, her understanding of the truth did not include Inuit creation legends.

We eventually paddled 58 km (36 miles) today, leaving us only 75 km (46 miles) from Kugluktuk (Coppermine). We would reach Muskox Rapids tomorrow. According to the Paddling Guide to the Northwest Territories, Muskox Rapids must be scouted.

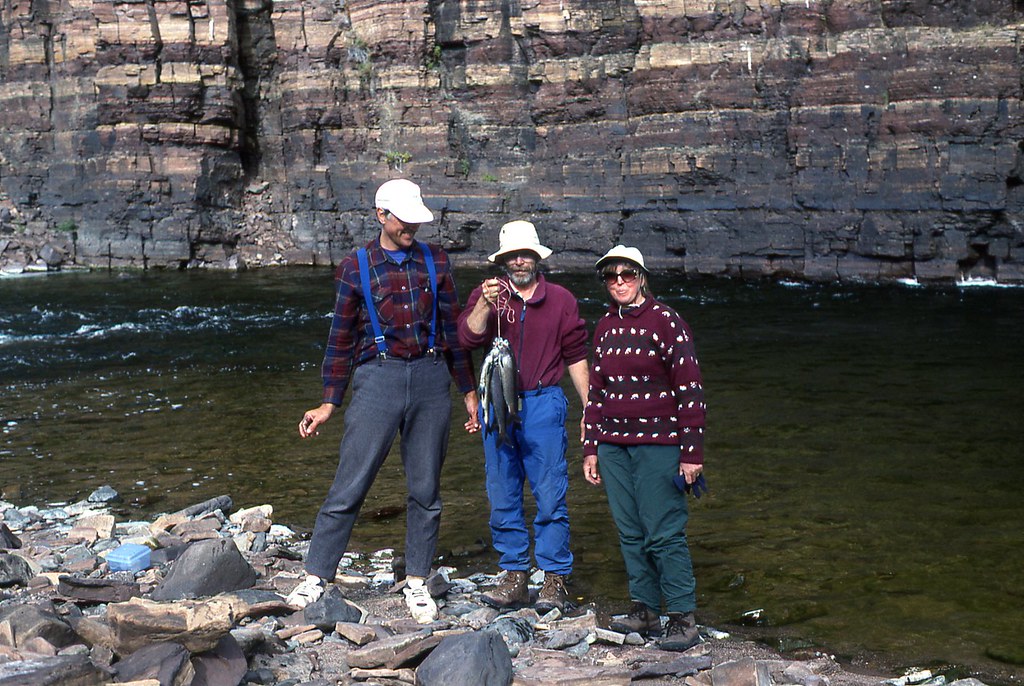

Carey and Kathleen scouting Muskox Rapids. River left looks open, but there is a ledge. Kathleen and I generally run rivers from inside bend to inside bend. We did here too. We paddled out to get beyond the ledge. Got our angle, and then powered back across the wave train into the eddy. So far so good.

We met our second paddlers of the trip here. A couple from Colorado camped on the left bank.

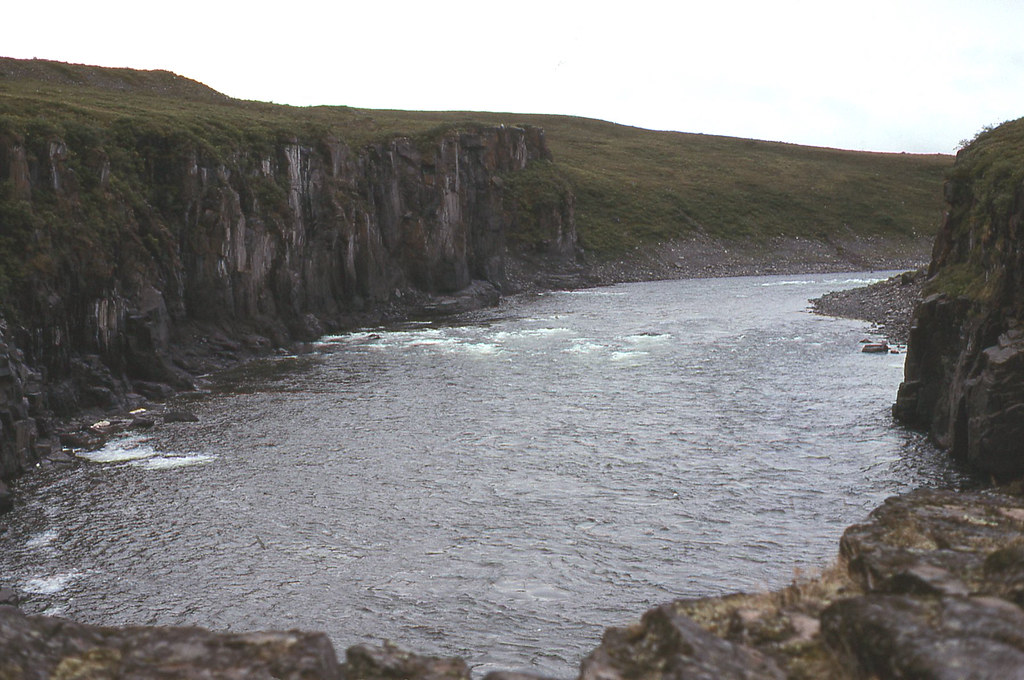

We ran Sandstone Rapids without scouting, and in the middle of the afternoon arrived here at Escape Rapids, the last rapid in the 100 km (60 mile) section that Franklin indicated had rapids frequent and dangerous. According to the Paddling Guide to the Northwest Territories, Escape Rapids is rated as Class III or IV, depending on water levels. The Paddling Guide also says.

Escape is the most difficult rapid of the trip and should be carefully scouted. The river flows through an S-curve gorge creating turbulence near the canyon walls on the outside curves. Two metre (6 foot) waves roll across the left limit at the first bend and a large ledge blocks passage on river right. Canoeists who decide to run this rapid should do so in empty boats.

We certainly would not follow the advice in that last sentence.If we are going to portage all the gear, we might as well portage the canoe as well. We would run or portage, not a combination of both. Besides, a loaded canoe might not be as maneuverable, but it is more stable. We decided to run. We selected our route. We needed only to ferry over to river right to avoid the large waves at the entry on river left and then ferry very aggressively back toward river left, using an eddy behind some large boulders. This would allow us to avoid the ledge extending out from river right.

We headed back to the canoes.

Carey and Janice went first. They always do in difficult water. Carey was arguably among the top five canoeists in the Province of British Columbia, where we lived in 1995. Carey was certainly the best canoeist I knew.

Back in the boats, we forward ferried over toward river right, slowly dropping down below the large waves on river left. We then began forward ferrying back to river left, hoping to drop just below the large waves. I was stroking very hard. I felt a genuine urgency to get back to river left to avoid going over the ledge on river right. You would have felt the same urgency, I am sure. I grunted involuntarily with each stroke, like a tennis player on television, putting everything I had into every stroke. We were now close to the boulder eddy, and gaining on Carey and Janice. How could we be gaining on Carey and Janice? We don’t gain on Carey and Janice. Perhaps we were too close to the eddy and should back off. No, that can not be it. Everyone knows it is almost always best to hit an eddy as high as possible. I stroked and grunted, stroked and grunted some more, and ran into the stern of Carey and Janice. Not a hard bump, or on purpose. We just wanted to get into that eddy.

Seconds later we were in that eddy. We turned downstream and paddled out of Escape Rapids.

Kathleen and I celebrated in the tent that night with fruitcake and brandy. Only three marked rapids and 34 km (21 miles) to go. We should be in Coppermine in two days, a full three days ahead of schedule.

After dinner that evening, we strolled away from camp to look back up toward the exit of Escape Rapids.

The next morning we prepare to portage around Bloody Falls.

Our first portage of the trip, which extended approximately 2 km ( a little over a mile) along the ridge on river right.

Kathleen and I usually carry three loads each to the end of the portage trail. It would be nice if she really could carry as much as two men, as Matonabbee had suggested to Hearne. I would have had to carry only two loads then.

The portage was actually relaxing, because we were able to enjoy side trips to the ridge top, very near to where Richardson first sighted the Coronation Gulf, now only 16 km (10 miles) away.

S

outh, back up the Coppermine, to near where Hearne first reached the Coppermine River as he travelled north and west from Fort Prince of Wales in 1771.

Hearne named this site Bloody Falls, because his guide, Matonabbee, led his Dene hunters into a massacre of Inuit as they lay sleeping in their tents on the left bank.

After finishing the portage, and enjoying an afternoon pot of tea, Carey and Janice paddled away from Bloody Falls, to try to catch the scheduled flight tomorrow from Kugluktuk (Coppermine) to Yellowknife.

Kathleen and I stayed behind, though, to enjoy the place and spirit of Kugluktuk, which I have read means Place Where the River Drops. I fished in the same spot where Inuit have also fished for thousands of years before me.

I had promised Kathleen that we would have fish for dinner. Every 15 minutes or so I hooked one, only to lose it near the shore. After nearly two hours I finally kept my promise with this White Fish

.

Bloody Falls remains a popular place to fish for the people of Kugluktuk (Coppermine). Kathleen and I were enjoying being all alone on the river. Soon after our meal, however, four groups from town arrived by powerboat. Five people stood on the left bank. Nine people clambered up the right bank. They had come to fish at the falls. Our few hours of being alone on the river were over.

The next morning, Kathleen and I paddled contentedly on a wide, smoothly flowing river that unceremoniously ended its journey at the arctic coast. No last rapids. No last drops or ledges. The Coppermine River just simply disappeared into the Coronation Gulf. We turned left around a point and headed west toward the town of Kugluktuk (Coppermine). Between sandy shoals and the shore, the water depth provided only a few centimetres (inches) of draft, and minutes later we were dragging our canoe across the tidal flats, in the rain. Our last physical struggle on the Coppermine River.

Kathleen and I had planned to spend two days visiting this arctic community, but the campground we head read about in a brochure did not have running water or toilets. The only hotel, the Coppermine Inn, was full. One bed and breakfast was closed for the season. The other was full.

Luckily for us, First Air had a scheduled jet service to Yellowknife that afternoon. Ninety minutes after boarding the plane, we were back in Yellowknife. That evening, seated in a restaurant enjoying pizza and wine, we reminisced about the 28 days we spent going overland from Fort Enterprise on Winter Lake to Point Lake, and then down the Coppermine River. We were glad that Carey and Janice had invited us. Kathleen and I would not likely have done this trip on our own.