Marc-Andre Pauze recently interviewed Garrett Conover and published the interview on his quarterly internet publication (marcpauze.net to subscribe). Some of Garrett’s observations might raise some eyebrows here, give it a read.

“There comes a time in the career of a wilderness canoe traveler when a trip down the river is no longer enough. Perhaps this river is not wild enough or remote enough, or perhaps it is frequented by too many groups. The traveler may have learned that most significant encounters with wildlife are often on high ground, beyond the banks of rivers and that the spiritual elements of even brief life in some part of nature shrinking wilderness require remoteness that is not easily accessible along major canoe-camping routes. The wilderness traveler, compared to the sport canoeist, may also experience pleasure in descending rapids, but this is only a small part of a larger perspective. The practicalities of long-term travel with significant loads require a more holistic and careful approach. This type of travel is rewarding for the person doing it, but its scope is infinitely wider than just a trip down the river.”

-Garrett Conover

In the field of backcountry wilderness exploration, Garrett Conover, woodsman, author and long-distance backcountry travel guide, is a leading authority whose philosophy transcends simple outdoor adventure . With a deep respect for nature and a commitment to traditional methods, Conover's approach to wilderness living is as much about fostering a deep connection with the natural world as it is about mastering practical skills.

With his partner, Alexandra, he founded North Woods Ways , a company specializing in traditional backcountry travel. Before creating North Woods Ways, the Conovers were fortunate to apprentice with a famous Maine traditionalist guide, Mick Fahey. Subsequently, they continued their apprenticeship with several "woodsmen" (and women), and lived with indigenous families from northern Ontario and the Innu of Nitassinan (Québec-Laradror), who still spent a lot of time in the Canadian backcountry.

In the 1990s, Garrett Conover literally wrote THE book on traditional winter camping with snowshoes, toboggans, canvas tents and wood stoves, long before the activity saw a resurgence of interest in recent years. He also wrote a book, Beyond the Paddle, explaining in detail the techniques that a traveler wishing to truly explore the backcountry must master. Mr. Conover learned his trade from an earlier generation of wilderness travelers and is known for his winter expeditions to Labrador and northern Quebec.

At the heart of Conover's philosophy is a fundamental respect for the natural backcountry territory. He views nature not only as a backdrop for recreational activities, but also as a sanctuary for personal development and spiritual renewal. In an age dominated by technology and urbanization, Conover advocates a return to simplicity, where the rhythms of nature guide our actions and shape our perceptions.

Over the years, Conover developed the skills of canoe travel, a practice that embodies the symbiotic relationship between man and his environment, and made it a way of life. For him, the canoe is more than just a means of transportation; it is a vessel for exploration, a conduit for communion with the natural world. Conover emphasizes the importance of mastering traditional canoe techniques, which allow travelers to navigate a land of lakes and rivers with grace and precision.

But Conover's vision goes beyond mere technical skill. He advocates a holistic approach to canoeing, which emphasizes mindfulness, stewardship and a deep appreciation of the wilderness. It advocates a human presence with minimal impact, inviting travelers not to leave traces and to tread the earth lightly. In his view, exploring the wilderness is not a conquest, but a communion, an opportunity to forge a harmonious relationship with the natural world. For him, nature is a sanctuary to be cherished and canoeing is more than a leisure activity, it is a way of life, a journey to discover oneself and the environment.

“Beyond being labeled a traditionalist, it has become difficult to create a language to express why traditional skills and equipment are better than what modern outdoor culture offers today. This culture is not educational, except that it wants to teach you to buy more and more things and to depend on an organization of nature rather than allowing you to develop knowledge to live in it.

-Garrett Conover

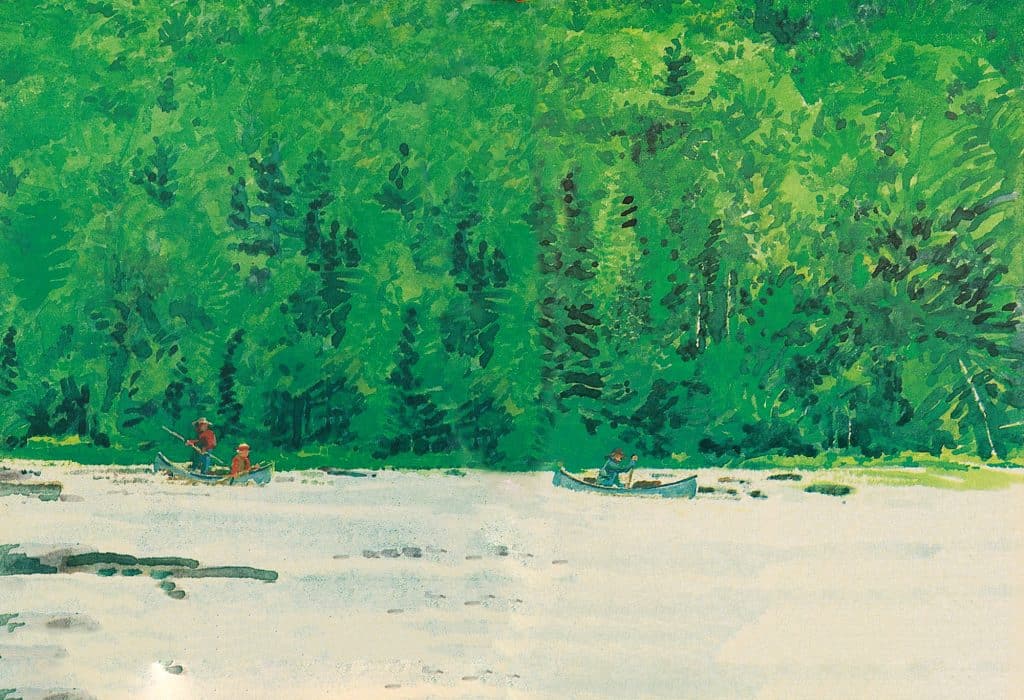

On the left Garrett Conover and on the right the technique of pole pushing (poling)

It was in the context of a report for L'Actualité that I came into contact with Garrett Conover. As the report touched on several aspects and the space allocated to me was limited, I was not able to do justice to Mr. Conover's thoughts. This is why I am publishing the interview we had here.

~~~~~~

MA P: Can you define for me what you consider to be canoe culture?

GC: The way I use and view the term canoe culture is related to serious, long-term travel that relies on mastering skills that enable truly ethical travel. Initially, it is very practical, the efficiency and energy savings maximize the pleasures of crossing wild and difficult terrain. In short, it makes what could be backbreaking work on some levels fun.

Next, and very much related, is about engaging with traditional skills that have been honed by generations of practitioners, and that come from the land itself. Because these skills were developed over hundreds, if not thousands, of years by people whose livelihoods depended on them, they will not be easily rediscovered by recreationists who spend only a few weeks or months on the land. during the year. And this, often at optimal times of the seasons.

Another factor that reduces the learning of many skills is the ease of access by road, train or bush plane. Many people who have made serious trips in this context have no concept of upstream travel, of complex navigation in trackless country, or of the special needs of transition between seasons, such as winter trips on snowshoes and toboggan that transition to canoe, or vice versa. It’s the difference between visiting a landscape and truly living in the land.

MA P: What would be the conditions conducive to the development of a culture of wild nature in our social construction?

GC: Society likes the symbol of wilderness, but I would say they don't really care about actual wilderness and have less and less, if any, interest in engagement in time and effort required for the components of a true commitment to it, namely:

MA P: Hap Wilson (another environmentalist-adventurer interviewed) told me that “the absence of enabling infrastructure is essential to maintaining wilderness values. Traditional paddlers and conservationists seek out this wilderness. They are willing to invest the time, effort and skill to get there, while modern recreational paddlers are looking for easier, well-developed destinations and places to show off their gear.” Is this what you call catalog culture? To what do you attribute the appearance of this culture?

GC: What I call “catalog culture” exploits this gap between the symbol of nature and wild nature itself, and does so with infinite expertise. The marketing myth is that you can buy expertise through sophisticated equipment. The distinction between the tool and some kind of badge of membership is deliberately blurred, creating the perfect addictive reward system for those who must have the latest, newest, flashiest gear. Hap Wilson ends his remarks with the clause on “showing off”. When I first read it, I found it funny, in a cynical way. Now, I think this is a rather astute observation, as dismaying as its implications may be.

MA P: What are the advantages of having favorable conditions for the development of a culture of wild nature and do you think this is possible thanks to a consumer-centered approach where nature is a commodity as we see it? meet more and more often?

GC: Furthermore, the combined cost, in time and money, of acquiring knowledge and mastering all skills is demanding. As a society, we seem to be too impatient. Plus, it’s out of financial reach for many people. The Temagami region's famous canoe camps were, and still are, experiences that usually last all summer. For campers for whom the experience resonates, these are years-long experiences. You start by learning the basics, practice on shorter, less demanding trips, and maybe even learn how to make some of the equipment you'll end up using. Subsequent seasons build on this, much like a longer-term apprenticeship or university study for four years or more would. Finally, you can take part in a real summer trip into nature. And for the most enthusiastic participants, you can start coming back every year as a paid leader working for the camp you so revere. This type of camp experience unfortunately doesn't come cheap. Wilderness, as is often the case, becomes the preserve of privileged people. Canoe clubs no longer provide opportunities to learn about traditional travel in its essence. They have become places of technical and specialized learning responding to the recreational tourism industry where stays in nature are very short. To develop a culture of nature we must go beyond the technical and sporting aspect of canoeing.

Anyone who achieves a high degree of mastery of skills and knowledge is not of interest to sellers of gadgets and equipment, nor to managers of protected areas which are increasingly becoming amusement parks too small to really be conservation areas. preservation of nature. We become too picky, demand too much autonomy, and are happiest with multifunctional equipment that we can maintain and/or make ourselves. We are generally immune to the manipulative nature of catalog culture and rarely need or want what is offered to us. When we buy things, it is usually from microenterprises and artisans who sell durable goods. Which brings us back to involuntary exclusivity; such things tend to be expensive even if they are worth it.

This group of people skilled in canoe culture is off the radar of the closest parks as well as smaller "wilderness" areas. Although we are allies in the conservation world, we do not need or want established campsites, marked and maintained portage trails, picnic tables, or any other infrastructure. We disappear on longer, more distant journeys.

I don't know how to bridge the various gaps mentioned above. As a society, we are at a low point in transmitting these values.

MA P: Thank you very much for your generosity. Your answers provide food for thought in order to escape the dictates of the industry of material consumption, fashionable activities, beautiful landscapes and the development of facilitating infrastructure, and thus see the activities in natural areas from the perspective of ethical preservation.

GC: Thank you for contacting me with such insightful questions and observations. You're trying to answer the least easy-to-answer questions about the wilderness. And of course, feel free to continue the conversation with me. Looking forward to it!

~

North Woods Ways

Wilderness culture through traditional canoe travel according to Garrett Conover

“There comes a time in the career of a wilderness canoe traveler when a trip down the river is no longer enough. Perhaps this river is not wild enough or remote enough, or perhaps it is frequented by too many groups. The traveler may have learned that most significant encounters with wildlife are often on high ground, beyond the banks of rivers and that the spiritual elements of even brief life in some part of nature shrinking wilderness require remoteness that is not easily accessible along major canoe-camping routes. The wilderness traveler, compared to the sport canoeist, may also experience pleasure in descending rapids, but this is only a small part of a larger perspective. The practicalities of long-term travel with significant loads require a more holistic and careful approach. This type of travel is rewarding for the person doing it, but its scope is infinitely wider than just a trip down the river.”

-Garrett Conover

In the field of backcountry wilderness exploration, Garrett Conover, woodsman, author and long-distance backcountry travel guide, is a leading authority whose philosophy transcends simple outdoor adventure . With a deep respect for nature and a commitment to traditional methods, Conover's approach to wilderness living is as much about fostering a deep connection with the natural world as it is about mastering practical skills.

With his partner, Alexandra, he founded North Woods Ways , a company specializing in traditional backcountry travel. Before creating North Woods Ways, the Conovers were fortunate to apprentice with a famous Maine traditionalist guide, Mick Fahey. Subsequently, they continued their apprenticeship with several "woodsmen" (and women), and lived with indigenous families from northern Ontario and the Innu of Nitassinan (Québec-Laradror), who still spent a lot of time in the Canadian backcountry.

In the 1990s, Garrett Conover literally wrote THE book on traditional winter camping with snowshoes, toboggans, canvas tents and wood stoves, long before the activity saw a resurgence of interest in recent years. He also wrote a book, Beyond the Paddle, explaining in detail the techniques that a traveler wishing to truly explore the backcountry must master. Mr. Conover learned his trade from an earlier generation of wilderness travelers and is known for his winter expeditions to Labrador and northern Quebec.

At the heart of Conover's philosophy is a fundamental respect for the natural backcountry territory. He views nature not only as a backdrop for recreational activities, but also as a sanctuary for personal development and spiritual renewal. In an age dominated by technology and urbanization, Conover advocates a return to simplicity, where the rhythms of nature guide our actions and shape our perceptions.

Over the years, Conover developed the skills of canoe travel, a practice that embodies the symbiotic relationship between man and his environment, and made it a way of life. For him, the canoe is more than just a means of transportation; it is a vessel for exploration, a conduit for communion with the natural world. Conover emphasizes the importance of mastering traditional canoe techniques, which allow travelers to navigate a land of lakes and rivers with grace and precision.

But Conover's vision goes beyond mere technical skill. He advocates a holistic approach to canoeing, which emphasizes mindfulness, stewardship and a deep appreciation of the wilderness. It advocates a human presence with minimal impact, inviting travelers not to leave traces and to tread the earth lightly. In his view, exploring the wilderness is not a conquest, but a communion, an opportunity to forge a harmonious relationship with the natural world. For him, nature is a sanctuary to be cherished and canoeing is more than a leisure activity, it is a way of life, a journey to discover oneself and the environment.

“Beyond being labeled a traditionalist, it has become difficult to create a language to express why traditional skills and equipment are better than what modern outdoor culture offers today. This culture is not educational, except that it wants to teach you to buy more and more things and to depend on an organization of nature rather than allowing you to develop knowledge to live in it.

-Garrett Conover

On the left Garrett Conover and on the right the technique of pole pushing (poling)

It was in the context of a report for L'Actualité that I came into contact with Garrett Conover. As the report touched on several aspects and the space allocated to me was limited, I was not able to do justice to Mr. Conover's thoughts. This is why I am publishing the interview we had here.

~~~~~~

MA P: Can you define for me what you consider to be canoe culture?

GC: The way I use and view the term canoe culture is related to serious, long-term travel that relies on mastering skills that enable truly ethical travel. Initially, it is very practical, the efficiency and energy savings maximize the pleasures of crossing wild and difficult terrain. In short, it makes what could be backbreaking work on some levels fun.

Next, and very much related, is about engaging with traditional skills that have been honed by generations of practitioners, and that come from the land itself. Because these skills were developed over hundreds, if not thousands, of years by people whose livelihoods depended on them, they will not be easily rediscovered by recreationists who spend only a few weeks or months on the land. during the year. And this, often at optimal times of the seasons.

Another factor that reduces the learning of many skills is the ease of access by road, train or bush plane. Many people who have made serious trips in this context have no concept of upstream travel, of complex navigation in trackless country, or of the special needs of transition between seasons, such as winter trips on snowshoes and toboggan that transition to canoe, or vice versa. It’s the difference between visiting a landscape and truly living in the land.

MA P: What would be the conditions conducive to the development of a culture of wild nature in our social construction?

GC: Society likes the symbol of wilderness, but I would say they don't really care about actual wilderness and have less and less, if any, interest in engagement in time and effort required for the components of a true commitment to it, namely:

- the skills required to spend very long periods of time in nature, in complete autonomy.

- the context.

- the story

- natural history

- recognition that for the first inhabitants it was a home, not a separate reserved place.

- and I would add to this all the philosophical reflections that usually develop for those whose engagement and curiosity are limitless in the natural world.

MA P: Hap Wilson (another environmentalist-adventurer interviewed) told me that “the absence of enabling infrastructure is essential to maintaining wilderness values. Traditional paddlers and conservationists seek out this wilderness. They are willing to invest the time, effort and skill to get there, while modern recreational paddlers are looking for easier, well-developed destinations and places to show off their gear.” Is this what you call catalog culture? To what do you attribute the appearance of this culture?

GC: What I call “catalog culture” exploits this gap between the symbol of nature and wild nature itself, and does so with infinite expertise. The marketing myth is that you can buy expertise through sophisticated equipment. The distinction between the tool and some kind of badge of membership is deliberately blurred, creating the perfect addictive reward system for those who must have the latest, newest, flashiest gear. Hap Wilson ends his remarks with the clause on “showing off”. When I first read it, I found it funny, in a cynical way. Now, I think this is a rather astute observation, as dismaying as its implications may be.

MA P: What are the advantages of having favorable conditions for the development of a culture of wild nature and do you think this is possible thanks to a consumer-centered approach where nature is a commodity as we see it? meet more and more often?

GC: Furthermore, the combined cost, in time and money, of acquiring knowledge and mastering all skills is demanding. As a society, we seem to be too impatient. Plus, it’s out of financial reach for many people. The Temagami region's famous canoe camps were, and still are, experiences that usually last all summer. For campers for whom the experience resonates, these are years-long experiences. You start by learning the basics, practice on shorter, less demanding trips, and maybe even learn how to make some of the equipment you'll end up using. Subsequent seasons build on this, much like a longer-term apprenticeship or university study for four years or more would. Finally, you can take part in a real summer trip into nature. And for the most enthusiastic participants, you can start coming back every year as a paid leader working for the camp you so revere. This type of camp experience unfortunately doesn't come cheap. Wilderness, as is often the case, becomes the preserve of privileged people. Canoe clubs no longer provide opportunities to learn about traditional travel in its essence. They have become places of technical and specialized learning responding to the recreational tourism industry where stays in nature are very short. To develop a culture of nature we must go beyond the technical and sporting aspect of canoeing.

Anyone who achieves a high degree of mastery of skills and knowledge is not of interest to sellers of gadgets and equipment, nor to managers of protected areas which are increasingly becoming amusement parks too small to really be conservation areas. preservation of nature. We become too picky, demand too much autonomy, and are happiest with multifunctional equipment that we can maintain and/or make ourselves. We are generally immune to the manipulative nature of catalog culture and rarely need or want what is offered to us. When we buy things, it is usually from microenterprises and artisans who sell durable goods. Which brings us back to involuntary exclusivity; such things tend to be expensive even if they are worth it.

This group of people skilled in canoe culture is off the radar of the closest parks as well as smaller "wilderness" areas. Although we are allies in the conservation world, we do not need or want established campsites, marked and maintained portage trails, picnic tables, or any other infrastructure. We disappear on longer, more distant journeys.

I don't know how to bridge the various gaps mentioned above. As a society, we are at a low point in transmitting these values.

MA P: Thank you very much for your generosity. Your answers provide food for thought in order to escape the dictates of the industry of material consumption, fashionable activities, beautiful landscapes and the development of facilitating infrastructure, and thus see the activities in natural areas from the perspective of ethical preservation.

GC: Thank you for contacting me with such insightful questions and observations. You're trying to answer the least easy-to-answer questions about the wilderness. And of course, feel free to continue the conversation with me. Looking forward to it!

~