- Joined

- Aug 21, 2018

- Messages

- 1,737

- Reaction score

- 1,946

This trip report is a continuation of a previous and recent trip report, "Our Winter of Content in Canada's Western Arctic," which is listed in "Winter Camping" on this site. In case you have not read that report, I would like to give a brief summary for context.

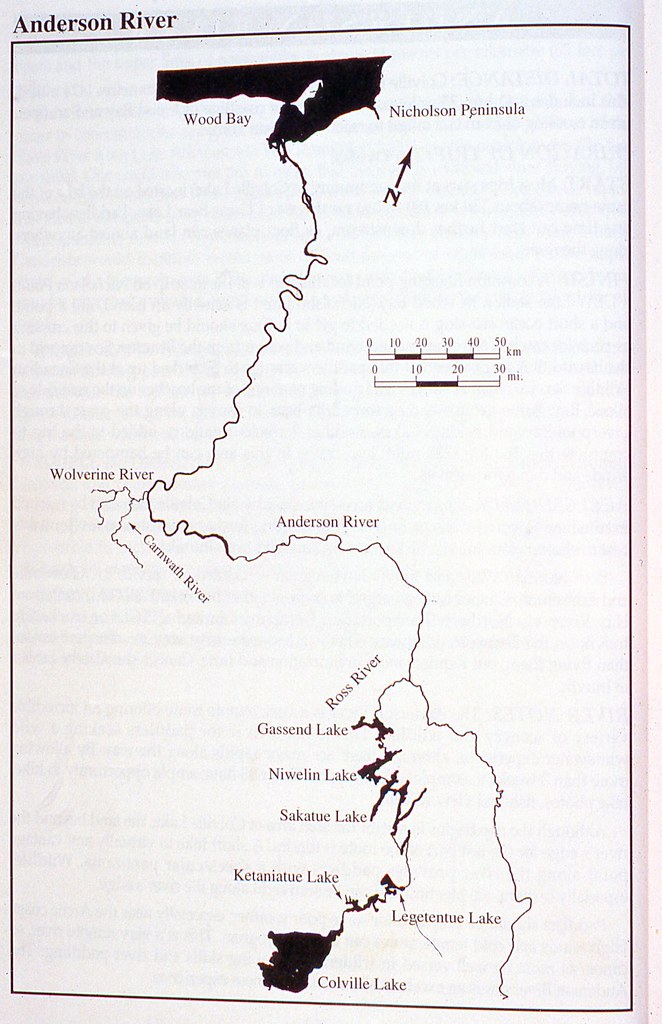

Kathleen and I began our Anderson River trip hunkered down on the frozen shores of Colville Lake, 100 km (62 miles) north of the Arctic Circle. We had arrived by Twin Otter on January 31, flying out of Inuvik, Northwest Territories, at -40 C. We unloaded our gear and supplies onto the metre-thick ice just 100 m from the one-room cabin that would be our home until the ice went out of the lake in mid-June.

(Note: -40° C exactly equals -40° F. How beautiful is that? You should also note that I ofter refer to metres in this TR, as Canada is metric. I referred to m above. If you prefer Imperial units, just substitute yards for metres. A metre is just a little more than three inches longer than a yard. For example, when I say that a saw a grizzly approaching from 250 m upstream, I didn't actually measure the distance. Two hundred and fifty yards might have been more accurate than 250 m anyway.)

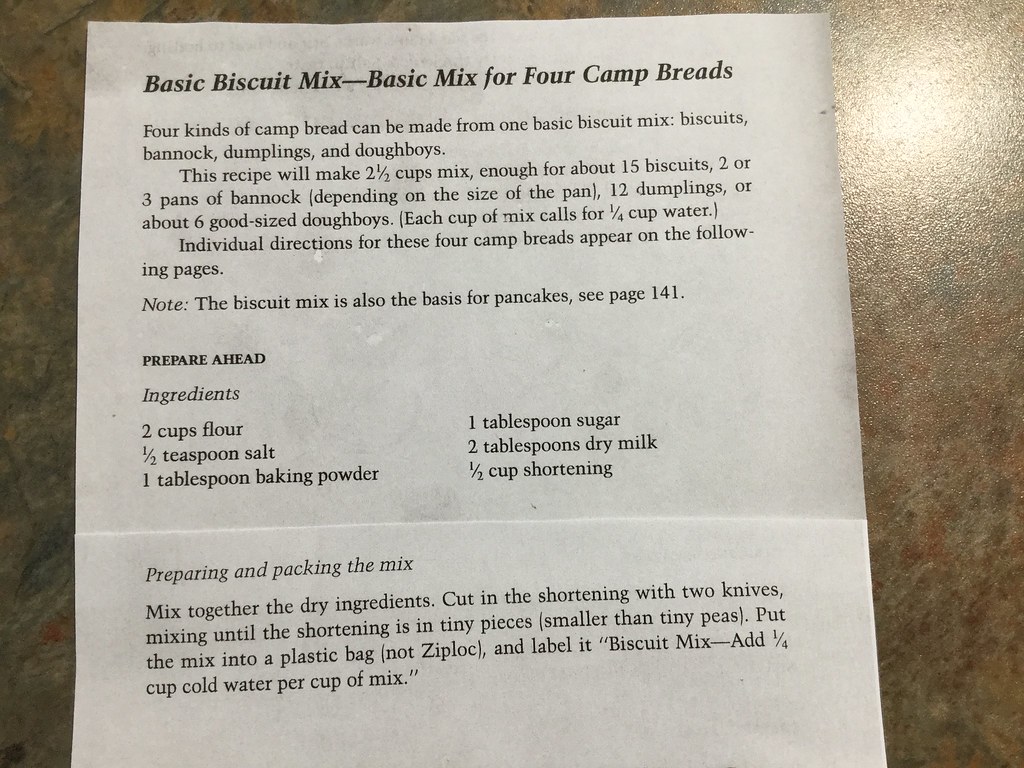

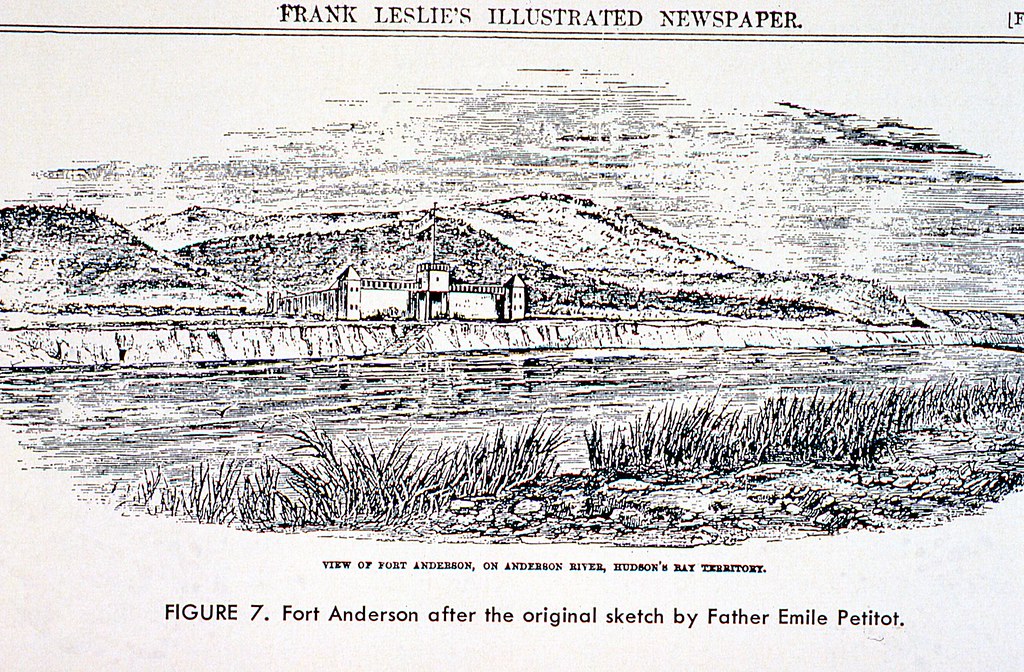

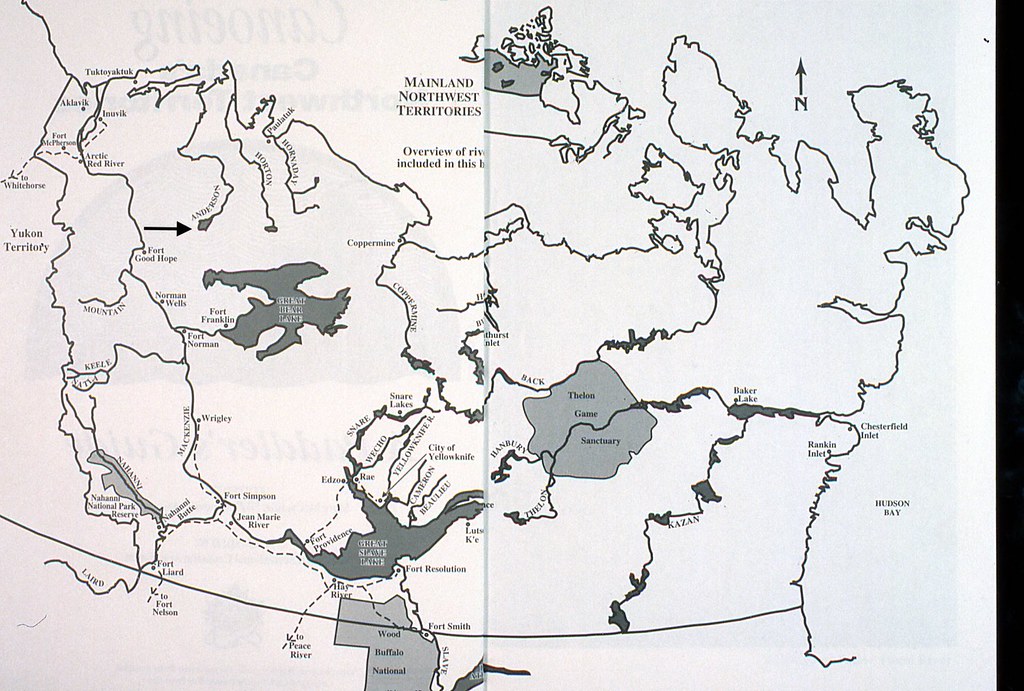

Diagram from Mary McCreadie's book, Canoeing Canada's Northwest Territories.

We had come to escape the crush of urban noise, concrete, and congestion. The nearest community of Colville Lake, with a population of only 90 people, lay 40 roadless km (25 miles) to the south. Otherwise, Kathleen and I were the only inhabitants in a 200-km (120 miles)-wide swath stretching 500 km (300 miles) north to the Arctic Ocean. This immense, silent world was ours alone to enjoy. We spent the next five, glorious months reading, sipping tea by the wood stove, snowshoeing, and revelling in the beauty of the unbounded boreal forest. We also looked forward to being the first people to paddle down the Anderson River that year (Note arrow in upper left).

For the first 2 ½ months we saw only 7 people and only for a few hours.

The world was ours and we spent the days traveling on our snowshoes, sipping tea by the fire, just enjoying the solitude and beauty.

Nine p.m., May 9, plus 5 degrees C (41 F). Break-up is beginning to happen, and we paddle more and more each day.

Eventually, as the sun’s warmth returned, and he snowpack began to shrink. On June 11, we paddled to town through shifting pack ice to make final arrangements for shipping our winter gear back to Inuvik.

We stopped to camp at 1:00 am the first night heading to town. Now maybe it was the cold of the winter. Or maybe it was our isolation from other people. But after a few months at the cabin, Kathleen’s crocheted bear, Beency, taken as a reminder of home, began to join in on our conversations. He was pleasant to have around, and was always joking. Whenever it was minus 40 he would remind us that it was his idea to have gone to Bermuda for the winter.

The town of Colville Lake was built entirely of logs from the surrounding area. Colville Lake is populated primarily by Hareskin Indians. Approximately 90 people lived in town. Flying into Colville Lake is most people’s first stop to canoeing the Anderson River.

After completing our business in town, we paddled back to our cabin on June 16. About half way back we found a great camping spot. You might keep this in mind if you ever paddle down the Anderson River. We stopped for dinner in the 30-degree (86 F) heat of the afternoon sun. There is no sign of the ice that clogged this route only 5 days ago. Summer has arrived instantly.

Near the north end of Colville Lake, we encountered a summer camp that had just been established by the Hareskin Indians, many of whom still followed a traditional lifestyle. During the past month, we had met many Colville Lake residents during their spring hunts for ducks and geese.

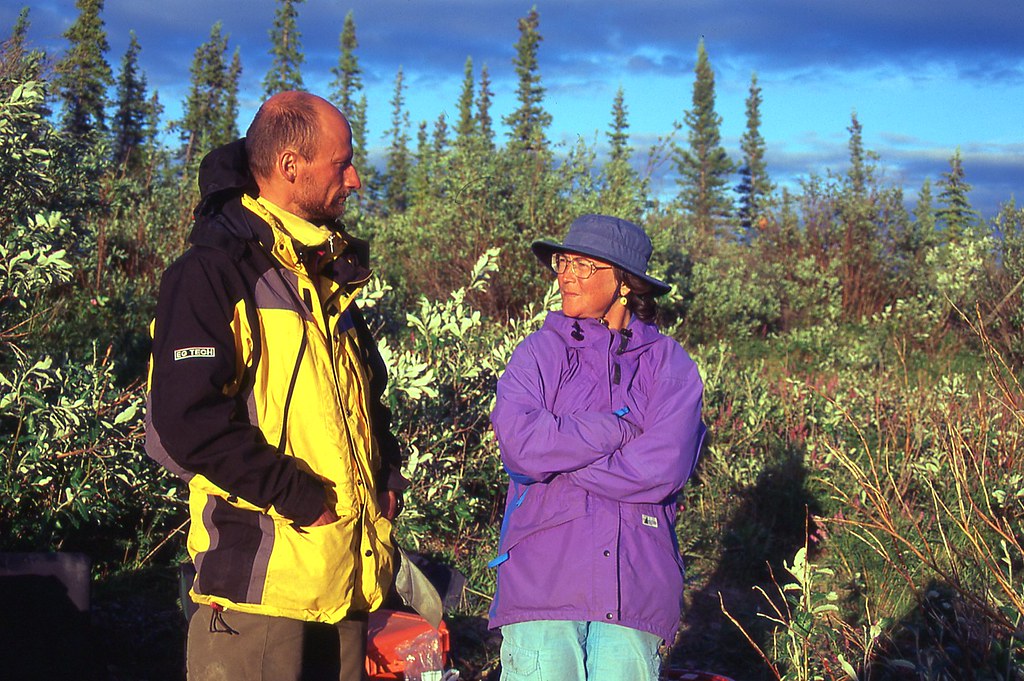

On June 19, at about 11:00 p.m., Richard and Charlie Kochon stopped by our cabin, in their powerboat, on their way to Legetentue Lake, about 35 km downriver. They intended to scout the area for moose, and do a little hunting.

“Would you like some tea?”

“Yep.”

They asked if we still planned to leave tomorrow, and wondered where we intended to camp. I spread out the topographic maps and pointed out the places on our intended itinerary, including our first camp in the “narrows” at Ketaniatue Lake. In fact, “Ketaniatue” means “Narrows Lake” in the local language.

“That’s not a good place for camping,” Richard said. “Willows too dense and tall.”

Richard pointed to another spot, on a point about 4 km (2.5 miles) beyond the narrows. “This is the first good spot for camping. You should camp here.”

We drank a few more cups of tea, and said goodbye to Charlie and Richard just after midnight.

I stood alone and silently as their boat vanished into the golden glow of a buoyant sun that floated softly on the northern horizon. A Bald Eagle soared majestically above Colville Lake. A beaver swam confidently through the narrows of the outlet. A northern pike broke water aggressively in the shallow warmth off our north dock.

Late the next afternoon, we were finally packed, and ready to descend the river. Beency insists that he wants to go with us. We have enjoyed our winter at the cabin, and will miss our life here. We are also very eager to begin paddling.

Diagram from Mary McCreadie's book Canoeing Canada's Northwest Territories.

We plan four weeks to paddle550 km (340 miles).

Change had been occurring all over the north, from the boreal forest, and beyond, out onto the tundra. During the first two weeks of June, blocks of ice and torrents of water had burst across the land. By the middle of June, the tumult and carnage of spring renewal had subsided. The grand rivers once again flowed stately between majestic banks. Like the seductive Siren of Greek mythology, the immortal Arctic summer called out to us. We could do nothing else than answer the sweet summons. Kathleen and I stepped into our canoe and paddled away from Colville Lake, down the Ross River towards its confluence with the Anderson River, which would take us north to the Arctic Ocean.

(Note: This is Kathleen at lunch, above the entry to Falcon Canyon. We are not actually there, yet. I just think the image goes nicely with the words above!)

We soon reached swiftly flowing water with two shallow rapids.

“I think we should head right, to the outside bend, where the deep water is.”

“Me too. How far right?”

“All the way up against the bank.”

“Well done. Now let’s head back left.”

Not bad for our first moving water since last September. It was nice to warm up with some easy Class I.

We rounded a point into Ketaniatue Lake, directly into the northeast wind, perfectly aligned with our route. Why do all northern canoe trips seem invariably to begin with a strong headwind? We paddled hard along the southeast shore, confirming Richard’s advice about the lack of camping. Willows grew thickly right from the water’s edge to the very top of the low ridge.

We drifted through the narrows, where a moose browsed nonchalantly, unaware of our downwind approach. Nearly 4 km (2.5 miles) later, on the first point of a horseshoe bay, we finally found a good camping spot, just where Richard said it would be. We dragged our gear up onto a peaty, tundra ridge. The continuing wind had now become our ally, as it kept all the bugs grounded. We gathered a few sticks of willow and birch for firewood to boil tea water, and to cook our pasta supper.

At 11:30 p.m. we lay in the tent, with a splendid view south, back up the lake. White blooms of Labrador Tea dominated the foreground tussocks, interspersed with pink splashes of Bog Rosemary. The showy white flowers of Cloudberry emerged from moist crevices. It had been a very satisfying day. We were 4 km (2.5 miles) ahead of schedule, snug in our tent, looking forward to the constant light that would accompany us for the next 4 weeks. In some sense, I felt that I was paddling and camping in my own backyard. We had lived in this country for nearly five months. Its vast horizons and endless purity made me happy just to be alive. Kathleen and I drifted to sleep, listening to the wind, and enjoying the sweet scent of Labrador Tea.

Last edited: