The next morning we loaded up the canoe and set off in a calm, sunny morning toward Bastion Rock, a little less than 15 km (9 miles) away. After trending southeast from our camp for a couple of hours, the Seal River turned due east. We were now just a little more than 1 km (0.5 miles) from Bastion Rock. A few minutes later, the river turned abruptly due south and the “Rock” soon came into view. Hap’s navigation chart indicated that the Class IV portion of the water was in river centre, with Class II on river right. The navigation chart also suggested a 250-m portage on river right.

Bastion Rock, now only 100 m (yards) away, sat at the bottom of the channel. Most of the water deflected back toward river centre, with high standing waves. Kathleen and I hugged the right bank and beached our canoe at the top of the side channel that swept around and below Bastion Rock on river right. As a river-running policy, Kathleen and I (almost) never enter side channels without scouting. Side channels have less water and are often clogged with debris and log jams. We got out, tied the canoe to some riverside rocks, and sauntered downstream to scout. Just as Hap suggested, the side channel offered Class II water, with a low ledge at the bottom of the drop.

“What do you think? Run or portage?”

“Run.”

Back in the canoe, we paddled down the side channel and re-entered the main current only minutes later, safely below the Class IV water. Way to go, Hap. Your navigation chart was bang on. Of course, that’s the way we would have run Bastion Rock anyway. Navigation chart or no navigation chart.

We are now looking back upriver toward Bastion Rock, on the left.

Two kilometres (1 mile) later we reached the next rapid, a river-wide ledge with a drop of maybe 1–1.5 m (3-4 feet). Hap listed the rapid as

“Class IV, scout!

” The rapid consisted only of the ledge. No rock gardens. I believe that we could have powered over the ledge right up against the left bank and paddled hard to escape the recirculating water at the bottom of the ledge. We have paddled ledges like this before. But not on wilderness canoe trips. Not when we are so isolated. Kathleen and I don’t capsize on wilderness canoe trips. We don't take chances. Besides, the portage was only a few metres (yards). No big deal.

We had bought a new Mad River Explorer for this trip. I had neglected to put bungee cords on the bow and stern decks of the canoe to secure the painters. The stern painter sometimes got caught in crevices. Mistake on my part.

After reloading the canoe, Kathleen and I enjoyed lunch, sunning ourselves on the rocky shore. Our greatest challenge of the day waited for us only about 10 km (6 miles) down the Seal River. Nine-Bar Rapids, which the Canadian Heritage Rivers brochure indicated was a “possible 3 km (1.5 miles) portage.” Nine-Bar Rapids, which Hap Wilson reported to be 3 km (1.5 miles) of “gruesome” Class III & IV.

That new canoe does look very nice!

Less than two hours later, the land up ahead dropped away as we approached Nine-Bar Rapids. We paddled cautiously along the inside bend of the left bank as we approached foreboding, turbulent ribbons of white. We eddied out, wrapped the bow line around a large, stream-side boulder, and hiked down the bank to scout Nine-Bar Rapids.

We walked single file, without speaking, both of us independently assessing the cascading challenge before us. The Seal River glowed beneath the lengthening, sunlit shadows of early evening. Golden-green tongues of water surged through an armada of impassive, dark, angular, rocky outcrops. Curling sheets of foam sparkled throughout.

We continued down the north bank until we reached a calm cove about halfway through Nine-Bar Rapids. “What do you think so far, Kathleen? Are you wanting to run or portage?"

"I think we can run what we’ve seen so far, Michael. Let’s go back to the canoe. We can paddle down to this cove and then scout the rest of the rapid.”

"OK."

We trudged back slowly along the north bank, planning our intended route. "I think this rapid requires only two major moves, Kathleen. First, we need to make a strong ferry out to the eddy behind the large rock at the top of the rapid. From there we can drift by the first jumble of rocks next to shore. Then we need to drive back hard to the left to avoid the ledge in the centre of the channel.”

Kathleen nodded. "I was thinking the same thing. After that we should be able to sneak along the left shore. The rest of that entire stretch down to the cove seems to have downstream Vs between all the rocks.”

We headed back to our canoe, turning around frequently to memorize the changing perspective of our checkpoints throughout the run. "See that greyish-looking, pyramid-shaped rock? We’ve got to stay just right of that before beginning to head back left. If we head back any sooner, we’ll never get through that first wall of rocks.”

"I see it. Are you confident with our choice to paddle this?”

"Yes.”

"Let's go, then.”

Back in our canoe we stretched our spray skirts snugly over the coaming of the spray deck cockpits. We glanced back one last time down the rapid, picked up our whitewater paddles, and then sat quietly, facing upstream. Kathleen on the left, me on the right. As usual, at the beginning of every difficult rapid, my mouth dried like a discarded chunk of Styrofoam baking in the summer sun. "It’s your lean, Kathleen.”

"I know. You just make sure you're powering hard when we cross the eddy line.”

We took a deep breath and thrust our blades fully into the water. With short, purposeful strokes, we ratcheted our canoe up to the top of the eddy. We crossed the eddy line at full speed, angled slightly outward, both of us leaning lightly downstream. The racing current grabbed the hull of our canoe, from bow to stern, and propelled us outward, across the rapid, toward the mid-channel eddy below the entry rock. With a few forward strokes, we rested safely in the haven of our first checkpoint. On either side of us the Seal River churned in a nerve jangling, clamorous din.

We cocked our heads downstream, searching for the greyish-looking, pyramid-shaped rock. "There it is,” said Kathleen, "but it certainly seems a lot more in river centre and closer to the ledge than when we were standing on shore.”

"Things always look different from the river. Do you want to leave the eddy on river right or river left?"

Seconds later we re-entered the rock-studded maelstrom, slowly working our way down to the greyish-looking, pyramid-shaped rock. We rode a narrow tongue of green water between two rounded boulders, slipped past the greyish-looking, pyramid-shaped rock, and angled our canoe toward the left bank. The ledge loomed ominously, its jaws wide open, only four canoe lengths below.

"Forward. Forward. More power!”

Knifing through the eddy below the greyish-looking, pyramid-shaped rock, our canoe sped toward the left shore. "OK. Enough power. We're by the ledge. Let's straighten out.”

We then ran with the current along the shore, slowing our descent by sideslipping into eddies below scattered rocks that offered clear, obvious passages. Moments later, we easily glided into the shallow, still water of the welcome cove, where we now rest. Halfway through. Only 1.5 (0.75 miles) km to go.

I stood on the bank and gazed downriver. It seemed that several routes existed, as far as we could see, anyway. "This doesn't look so bad, Kathleen. Not many rocks at all. Mostly shallow gravel bars, and some standing waves no more than a metre (3 feet) high. What do you want to do? Do you want to walk down the shore to scout the rest of the rapid?”

“The first half wasn’t so bad, Michael. And this looks better. Why don’t we just work our way down. The water’s not too pushy. We’ll just go from one eddy to the next. We can always get off if we can’t see the next eddy.”

We settled back into the canoe, and the rest of the rapid proved fairly easy, except for a lift-over at the ledge at the end of the run. We then paddled into the calm water at the east end of the Great Island at 8:30 p.m. After our successful run of Nine-Bar Rapids, we were feeling quite relaxed, floating comfortably in the early evening. As we slipped past a fairly large rock, its top suddenly rose up and leaped into the water. Quite startling. We normally don’t expect rocks to rise up and leap. Although we were nearly 140 km (85 miles) from Hudson Bay, the leaping rock was a seal, which are common on the river, and for which the river was named.

Just before 10:00 p.m., after 11 hours on the water, we arrived at the Environment Canada water monitoring cabin, which was rebuilt after the 1994 wildfire that burned for three months and consumed 250,000 ha (620,000 acres). As no one was home, we moved in to enjoy the luxury and comfort of sitting on chairs while eating our supper at a table. Just before crawling into our sleeping bags, we toasted our day’s success with a glass of brandy, savoured beneath the bright light of a Coleman lantern. Almost like sitting in one of the fashionable pubs along Vancouver’s upscale Robson Street. Well, not quite. We didn’t cradle elegant brandy snifters in our hands. There is a limit to how elegant I can feel while drinking brandy from a plastic cup.

Kathleen and I slept fitfully in the cabin, as mosquitoes harassed us all night. Very few bush cabins, if any, are bug free. We talked briefly about going outside to put up our bug-proof tent. That seemed like a lot of trouble, though. We applied more bug dope, burrowed deep into our sleeping bags, and toughed it out until morning. Bush cabins are often not as comfortable as you might think or hope.

We left the Environment Canada water monitoring cabin at noon and drifted lazily, about 12 km (7.5 miles), down to Daniels Island, where we stopped for a snack at 2:00 p.m.

The thermometer read 38 degrees C (100 degrees F) on the sun-drenched beach. Too hot to paddle on.

We decided to make camp. We lugged our gear up on the ridge to pitch our tent in the shade of a few trees. We dozed and hoped that the heat would soon end.

During supper, we decided to forgo our one remaining scheduled rest day on the river and push on to Hudson Bay. That would give us one full day at the bay to assess its potential for paddling to Churchill.

The sun shone unbearably hot all afternoon, most of which we spent seeking shelter in the shade. At 10:30 p.m., a moose, likely to escape the heat and the bugs, swam into the river and crossed beneath the blazing sun, which was sinking slowly toward the northwest. We hoped tomorrow would cool off.

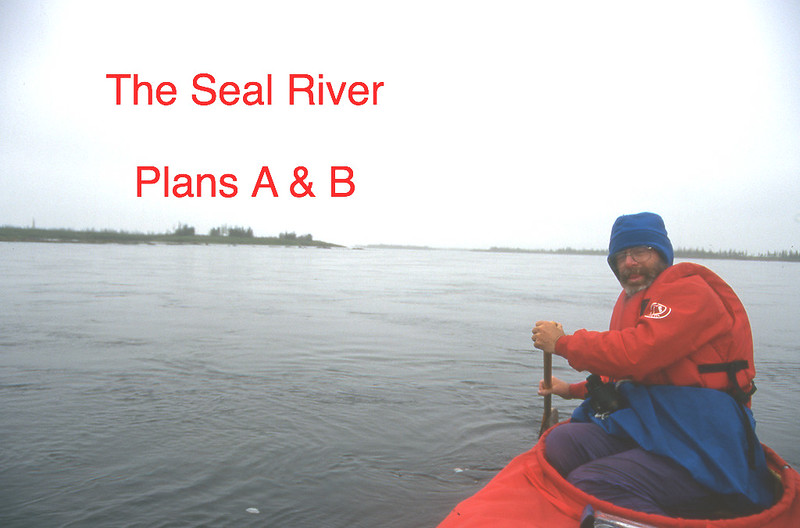

We woke to a cool 8-degree C (45 F) morning. The wind had shifted to blow in from the east, bringing fog and mist from Hudson Bay, which now, for the first time, seemed to lie, ominously, in wait for us.

Our lunches are usually very simple. Often Top Ramen soup heated up with water boiled at breakfast, and then kept hot in our thermos. Cheese and crackers. Dried pineapple rings. Gorp. Quick and easy.

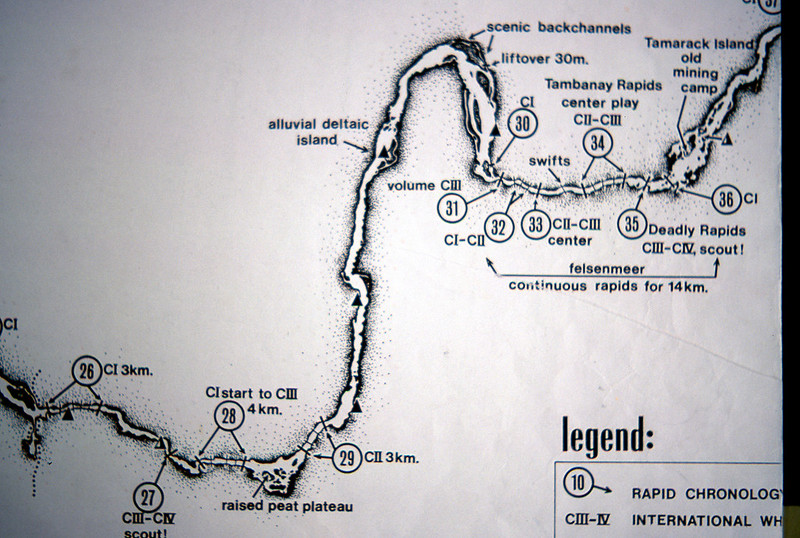

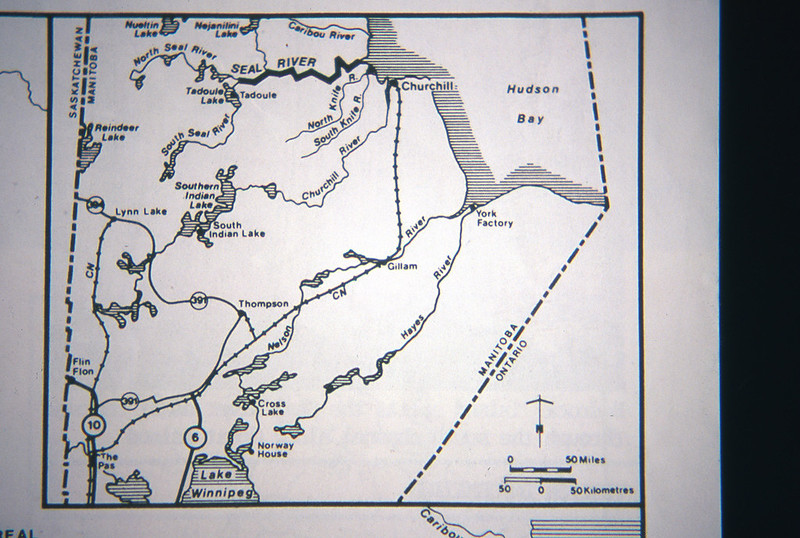

Late in the afternoon, we approached the "raised peat plateau."

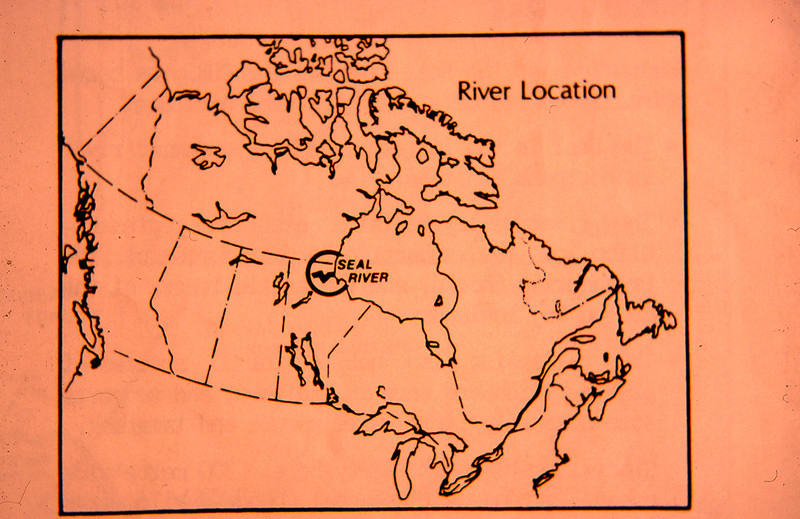

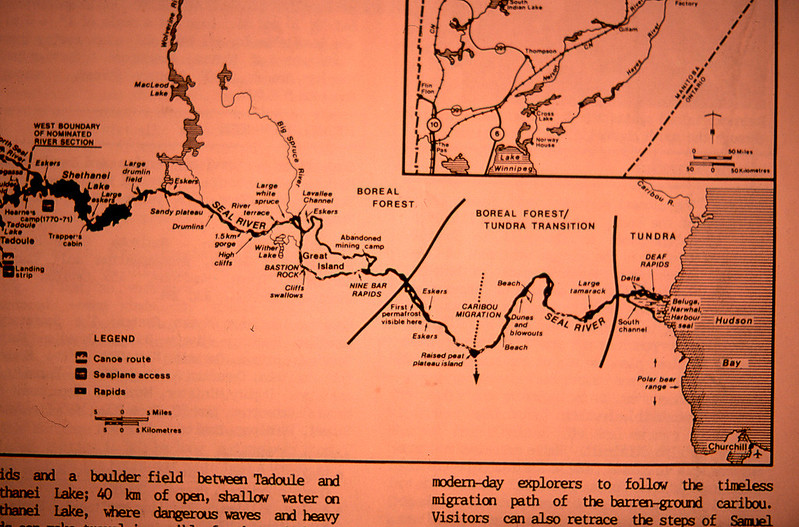

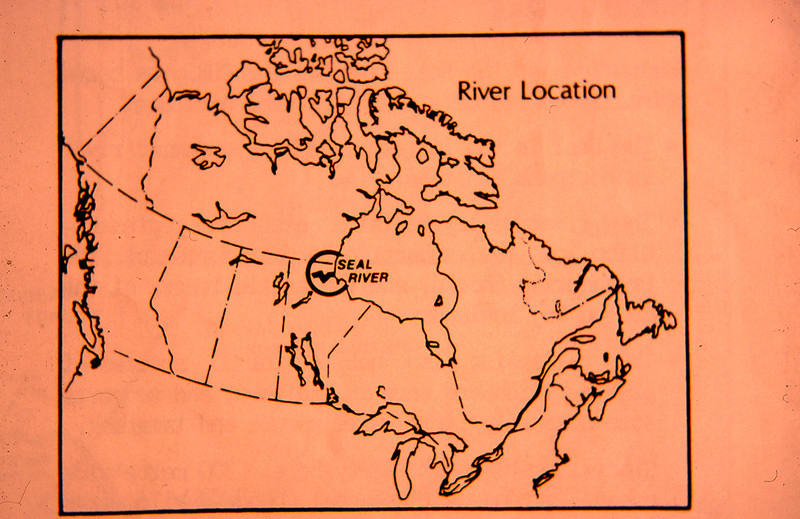

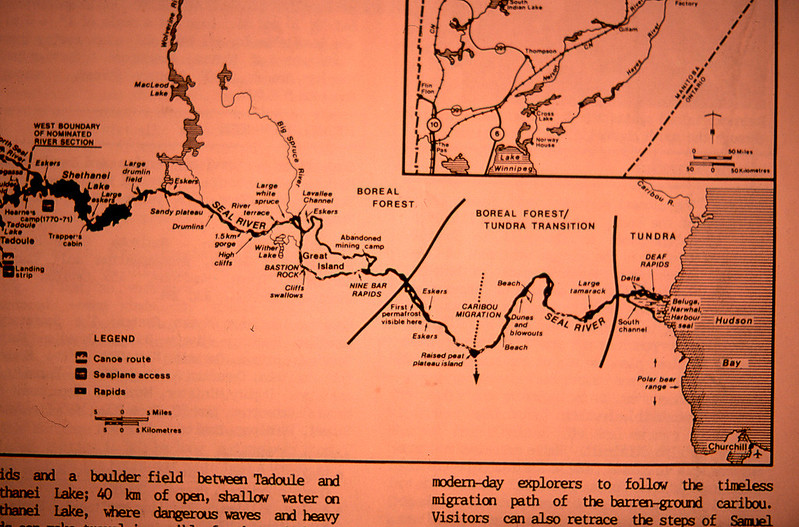

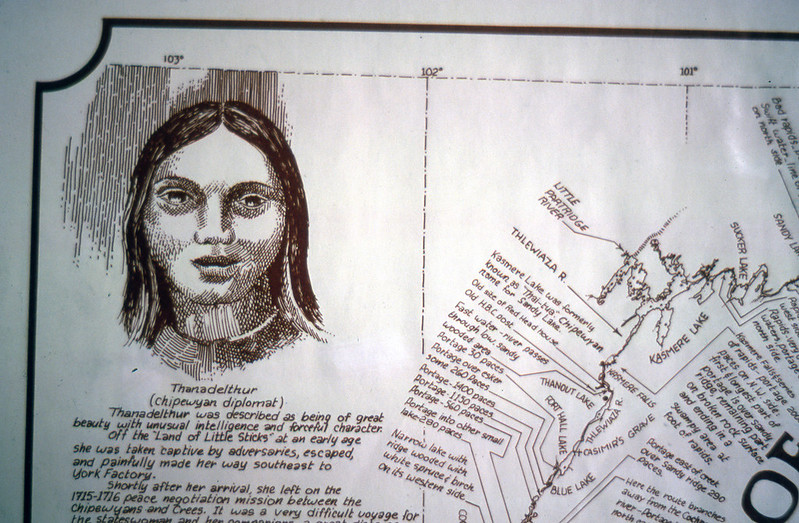

For reference, note the "raised peat plateau" in the southern-most portion of the river. We are now in the boreal forest/tundra transition, and are making good progress toward Hudson Bay.

Based on information in E. C. Pielou’s book

A Naturalists’ Guide to the Arctic, the peat plateau likely formed 5,000−10,000 years ago. I paraphrase:

When the accumulating peat from dying, but not decaying sphagnum moss becomes thick enough, it fails to thaw in summer, becoming a flat slab of permafrost. The ground above the frozen slab starts to rise, (1) because the water in the peat expands on freezing, and (2) more water migrates toward the expanding slab. These expansions cause a raised dome to appear.

As it rises, the dome becomes better drained and starts to dry out in summer. Its surface cracks; rain and warm air reach its frozen core, and before long the centre thaws and the whole structure then erodes and collapses.

As Kathleen and I stood on the peat plateau, looking down the Seal River, the sun appeared for the first time that day. We hoped that the hot, sunny weather that we’d been cursing only yesterday would soon return.

After paddling about 35 km (22 miles) today, we stopped to camp at 6:00 p.m., just north of the raised peat plateau. This was exactly where our tentative itinerary listed us to be today. We also successfully ran six more of Hap’s rapids, including a Class III and a Class III–IV. At our water levels, we would not have rated either of these rapids as that difficult.

We both felt tired and ate a simple supper of cheese, plus soup cooked quickly on our stove rather than over a campfire. We retired to the tent immediately afterward to sip brandy, to munch on fruitcake, and to study our plant books and maps. Although tired, I was satisfied and content. I was even comforted by the thunder rolling toward us from across unbroken tracts of boreal forest.

For the second evening in a row, a mist formed over the river, perhaps an influence of Hudson Bay, which now lay only 60 km (37 miles) due east. Approximately 90 km (56 miles) away by river.

The mist persisted throughout the night, and hung heavily over our morning camp. We dozed, and then lazed through breakfast, hoping for the fog to lift.

Kathleen and I generally build very small fires. Just enough to heat our food and clean the dishes. We don't burn a lot of wood, and don't even take a saw or axe anymore. If the wood is too long, we just simply put one end in the fire, and the slowly feed the longer portion in as needed. We like to cook on sand. We scoop out a trench below the grate. Before leaving camp, we cover the charred wood with sand, and smooth it over. One would hardly know that we had cooked there.

We finally paddled away at 12:30, despite poor visibility and a steady headwind.